Milking the cash cow with carbon credits

INDIA is making strides towards achieving the target of net zero carbon emissions by 2070 through a variety of initiatives. These include endeavours in solar energy, Lifestyle for Environment (LiFE), green hydrogen, electric vehicles (EVs), waste-to-wealth, organic and natural farming. India is also launching a domestic compliance carbon market to facilitate trading of carbon credits.

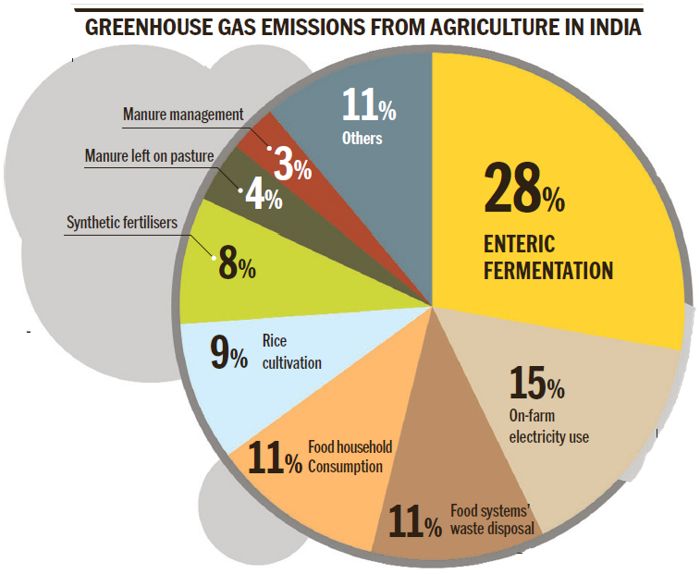

Dairy farmingIndia has experience in carbon trading, particularly in wind energy, biogas production, clean cooking stoves and agricultural land management. While carbon projects in agriculture have been less frequent, their number has increased of late. India is implementing sustainable agriculture practices, including zero tillage, alternative wetting and drying, direct seeding of rice, and integrated nutrient and residue management. While this progress is encouraging in terms of reducing carbon emissions and addressing climate change, it is crucial to assess whether these efforts are adequately targeting the highest greenhouse gas emitters in the agriculture sector or merely focusing on readily available solutions? This is a critical question that needs to be addressed to ensure that we effectively combat climate change.

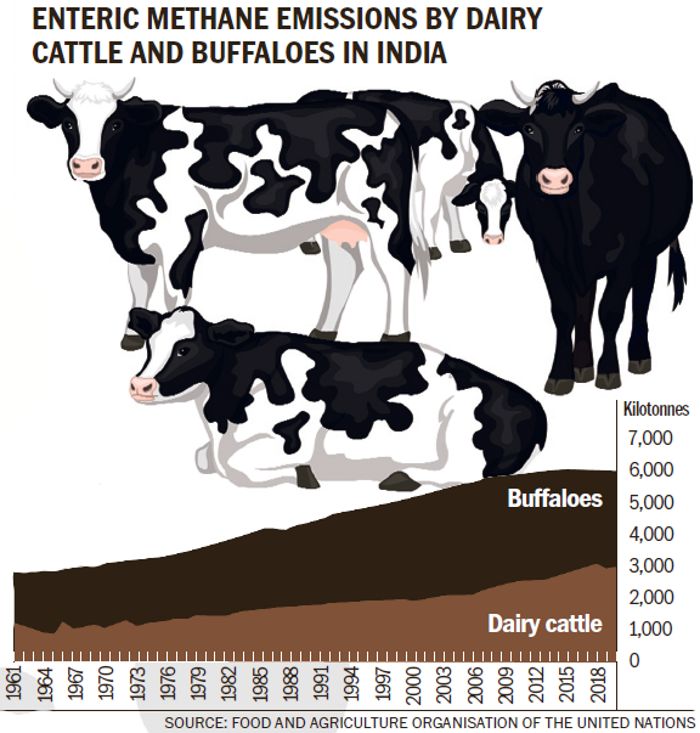

Given the expected increase in the bovine population due to the rising demand for milk and milk products, these emissions are expected to continue increasing. According to an article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, enteric methane emissions must be reduced by 11-30% by 2030 and 24-47% by 2050 compared to the 2010 levels to meet the 1.5°C target.

To effectively curb emissions, India must prioritise producing more milk per unit of methane emitted. Achieving this goal necessitates providing animals with high-quality and abundant feed and implementing methane emission mitigation strategies. However, the challenge lies in the widespread adoption of these strategies, as the traditional practice of subsidising them through government schemes may prove ineffective in the Indian dairy sector. Two potential solutions can be explored: leveraging the large cooperative network to implement emission reduction strategies through village-level dairy cooperative societies and utilising carbon markets to incentivise farmers through carbon credits.

A recent report of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) highlights two potential game-changers in combating enteric emissions: 3-Nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) and Asparagopsis taxiformis (red seaweed). 3-NOP has been found effective in ensuring animal welfare and food safety. According to a meta-analysis, including 3-NOP in livestock feed could reduce enteric methane emissions by 30%. Additionally, a study in India suggests that providing a balanced feed can lead to 15% reduction in emissions.

It seems logical that if there are solutions available and there is a demand for carbon credits, the livestock sector, being the highest emitter, should have the highest number of carbon farming projects. After all, greater reductions can be achieved when emissions are high due to the high base effect. However, it is astonishing that no project in India is currently aimed at reducing enteric methane emissions.

There are registered biogas projects with 4 million-plus carbon credits already issued. However, livestock manure accounts for only 10% of livestock emissions, while the potential for generating carbon credits through reducing enteric emissions is much higher. Some argue that the challenge lies in measuring and monitoring enteric emissions, particularly those involving smallholder farmers.

To address this issue, a simple digital MRV (measurement, reporting and verification) system should be developed, either standardised or tailored to specific locations, and made available in the public forum for project developers to implement. Research organisations such as the International Livestock Research Institute and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, with their expertise and experience in dealing with enteric emissions, should take up this task.

Globally, the Verified Carbon Standard Registry currently lists only two registered projects (in the UK and Switzerland), with three more in the pipeline — all in the USA. It is high time we redirected our attention towards enteric methane reduction. By doing so, we can make a substantial positive impact on both the environment and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers.