More Milk, Less Money: India’s Dairy Crisis

With the release of the BAHS 2025 summary report, I felt compelled to deep dive into its findings and reflect on the real progress and challenges facing India’s dairy sector.

Over the last six years, India’s dairy sector has continued to consolidate its global leadership, even as deeper structural challenges around farmer incomes, sustainability, and productivity have become increasingly evident. An assessment of trends in milk production, cattle population dynamics, budget allocations and farmer value realisation reveals a sector that is expanding steadily in volume terms but struggling to translate this growth into higher real incomes for the millions of households that depend on dairying. The fundamental policy question now is not merely how to increase national milk output, but how to ensure that production growth yields meaningful improvements in farmers’ economic well-being.

Production and Cattle Population: The Story of the Last 5–6 Years

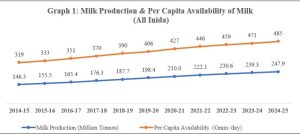

Milk production in India has risen from nearly 198.40 million tonnes in 2019–20 to 247.87 million tonnes in 2024–25, an increase of almost 50 million tonnes in half a decade. This reflects an average annual growth rate of around 3.5 to 4 percent, a rate that has remained relatively stable despite the disruptions caused by the pandemic, fodder shortages, and climate-induced heat stress. Importantly, this expansion has been driven more by increases in yields than by increases in animal population. Livestock census figures show that the cattle population has remained broadly stable, rising only marginally between the last two census rounds.

The real transformation during this period has come from the changing composition of the milch herd. Crossbred cattle, which deliver significantly higher yields, now contribute over 30 percent of India’s total milk, while indigenous and non-descript cattle—collectively accounting for just above 20 percent—continue to decline in their share. Buffaloes remain central to India’s dairy landscape, collectively contributing around 43 percent of national milk production, with indigenous buffaloes alone accounting for 31.18 percent in 2024–25. This shift towards higher yielding breeds represents a significant structural improvement, but it also brings with it concerns around feed demand, heat stress and sustainability.

Budget Spending and Growth Outcomes: Are They Connected?

The Department of Animal Husbandry & Dairying’s (DAHD) Budget Estimates (BE) increased steadily from about Rs 2,932 crore in FY2019–20 to Rs 4,521 crore in FY2024–25, representing a 54 percent rise in nominal expenditure. When national milk production figures for the same period are compared with these budget allocations, a simple regression reveals a surprisingly high statistical correlation, with an R² value of approximately 0.87. On the surface, this suggests a strong relationship between public spending and output expansion. However, such an interpretation must be approached with caution. Central government spending is a relatively small component of the overall dairy economy, which is shaped far more by state budgets, cooperative investments, private dairy processors, feed markets, fodder availability and climatic conditions. Moreover, many central schemes—such as breed improvement, disease control, and infrastructure development—have long gestation periods, meaning their effects are not immediately visible in year-on-year production growth.A more revealing picture emerges when examining the value of milk in the economy. Using BAHS data for the milk group’s contribution to GDP, the nominal value per litre of milk increased from approximately Rs 24.5 per litre in 2011–12 to nearly Rs 43 per litre in 2021–22, reflecting inflation and market expansion. But when adjusted for inflation using constant 2011–12 prices, the real value per litre has remained almost flat at around Rs 24 per litre throughout the decade. This indicates that although the total value of milk has grown due to higher production volumes and general inflation, farmers’ real returns per litre have not improved significantly. This stagnation of real value is one of the most important and under-discussed findings in the sector.

What’s Going Good, Bad, and Ugly

The broad trajectory of India’s dairy sector is marked by contrasting realities. On the positive side, the country has achieved steady production growth even during years of climatic volatility, enabling per capita availability to rise to nearly 485 grams per day. The steady shift toward higher-yielding crossbred cattle is another encouraging development, and it reflects the impact of improved artificial insemination services, better breeding strategies, and heightened farmer awareness. The cooperative and private sectors have also continued to expand their collection networks, chilling infrastructure, and value-added product lines, reinforcing India’s dominant position in the global dairy economy.Yet beneath this progress lie some structural weaknesses. Foremost among them is the stagnation of real farmer income. Despite producing far more milk than a decade ago, dairy farmers are not earning proportionately more in real terms. The cost of feed and fodder has escalated faster than the real price they receive per litre, narrowing margins and increasing financial vulnerability. Environmental pressures are also intensifying, particularly in regions where buffalo-based dairying dominates. Large buffalo herds require substantial water and feed resources, and their concentration in specific states contributes to over-extraction of groundwater and ecological stress.

Regional imbalances persist, with states like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra together contributing more than half of India’s milk, while eastern and northeastern regions remain underdeveloped in dairy infrastructure. An emerging challenge, often underestimated, is the rise of alternative proteins, supported under India’s BioE3 framework. Precision-fermentation dairy substitutes could, in the long term, disrupt demand for conventional milk in high-income urban segments, putting pressure on the traditional dairy value chain if not properly regulated.

There are also deeper systemic risks that could become “ugly” if left unaddressed. Misinformation regarding milk and dairy products has increasingly shaped consumer perceptions, particularly on digital platforms. Periodic anxieties around adulteration, lactose intolerance, or cholesterol—often exaggerated or poorly contextualised—have contributed to demand fluctuations in certain markets. In addition, rising input costs, labour shortages in rural areas, and the absence of consistent long-term price signals could push smallholders either to exit dairying altogether or to intensify unsustainably, both of which carry economic and ecological consequences.

Future Projections: What Is Good for India—Higher Production or Higher Farmer Income?

Looking ahead, India faces two strategic pathways. The first involves pursuing higher production growth in the range of 5–6 percent annually. Achieving this would require significant herd expansion or high-intensity production systems based on heavy feed utilisation, both of which would impose substantial environmental burdens. While this pathway might support processors and exporters, it risks amplifying groundwater depletion, methane emissions, and feed scarcity.The alternative—and more sustainable—path is to target a 3.5–4 percent annual growth rate anchored primarily in productivity improvements rather than herd expansion. This approach emphasises genetic improvement, scientific feeding, climate-resilient practices, and better market integration. It is also far more aligned with the national imperative of enhancing farmer incomes. The evidence is clear: raising production alone does not increase real income per litre. What matters is increasing the value per litre for farmers and decreasing their cost per litre through improved efficiency and reduced wastage. Under this second pathway, production and income can rise together, but only when the emphasis is on yield, quality, and value addition rather than sheer volume.

Policy Recommendations for a Sustainable and Farmer-Centric Future

For India to build a dairy sector that is both economically rewarding and environmentally sustainable, policy must shift from volume-centric targets to value-centric outcomes. The national growth target should be anchored at 3.5–4 percent, balancing nutritional needs with ecological stewardship. Government budget allocations should be guided by a calibrated matrix that measures expenditure per million tonnes of production and per milch animal, thereby linking financial input to measurable outcomes. A larger share of the budget must flow into climate-smart dairying—fodder development, water-efficient systems, disease control, methane mitigation strategies, and improved genetics—rather than fragmented schemes that yield limited long-term returns.Strengthening farmer incomes also requires more robust market mechanisms. This includes expanding cold-chain infrastructure, incentivising quality-based milk pricing, supporting dairy exports, and fostering regional value-added dairy clusters that can generate premiums for farmers. Only when farmers receive a higher real return per litre, supported by lower production costs and better productivity, can India truly achieve sustainable growth in the sector.

Conclusion: The Question That Must Guide Our Next Phase of Research

India has successfully doubled its milk output over the past two decades—but has it doubled the income of the farmers who produce that milk? The evidence so far suggests a widening gap between volume growth and income growth. This leads us naturally to the central question that should frame our next research paper: Has dairying genuinely advanced the national goal of doubling farmers’ income, or have we only doubled the milk without doubling the prosperity of those who produce it?From here, the next stage of analysis must probe deeper into milk price behaviour, farmer income trends, and the true impact of dairying on rural financial wellbeing. This is where the next phase of our research must begin.

Source : Dairynews7x7 Dec 1st 2025 blog by Kuldeep Sharma Chief editor Dairynews7x7