Invoking the green revolution to justify the new farm laws may not be right

Last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi hardened his government’s stand on the farm laws. In the Rajya Sabha, during his reply to the President’s address, the Prime Minister asserted that the farm laws wouldn’t be repealed, although the government was open to negotiations. Modi made his case for reforms by invoking former Prime Ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri, Chaudhary Charan Singh and Manmohan Singh.

In his long speech, lasting for over an hour, of which 25 minutes were devoted to the controversial farm laws, Modi likened the farm reforms to the green revolution of the mid-1960s and 70s, saying that revolution too had been met with resistance and opposition, just as the three farm laws now. The Prime Minister also gave the example of Operation Flood or the White Revolution that had made India the world’s largest milk producer, accounting for 20 per cent of the world’s production.

PM speech

A day after his speech in the Upper House, his response to the motion of thanks on the President’s address in the Lok Sabha was overtaken by angry protests from the Opposition when he spoke of the farm laws. The Opposition shredded him for over two days for comments like ‘Andolan Jeevis’ (professional protesters) and ‘Parjeevis’ (parasites) made in Parliament during his earlier address.

What followed were loud protests and a huge altercation, which the Prime Minister said was a ‘planned strategy to drown out reason to hide the truth’. Admitting that change would ‘always raise doubt’, the Prime Minister repeated the same old stuff: “The farm laws will not bring down any farmers. No mandi has been shut nor minimum support prices (MSP) stopped.” But the farmers are not impressed. Disinclined to accept the Prime Minister’s assurances and promises, they are continuing with their protest, which has become even stronger with larger participation of farmers in mahapanchayats in many states in solidarity with the farmers at Delhi’s borders.

Green revolution

Invoking the green revolution to justify the new farm laws may not be right, given that there is little comparison between the two, as also between the India of 1960s and the 2020s. The 1960s were the time when India was in the throes of massive food shortages, monsoon failures and agriculture crisis. That was also the time when the country depended on America’s PL 480 scheme, a law especially enacted for India, under which the US would send India foodgrain – 3 to 4 million tonnes of wheat – so that Indians wouldn’t starve.

That was also the time when Indian planning was obsessed with heavy industry and agriculture was seen through land reforms, community development, cooperativism and motivation. It is true that peasant movements led by the Left parties in the post-Independence era were in favour of land redistribution from the landlord to peasants to tackle the food crisis and therefore, were fiercely opposed to the idea of the green revolution.

But the Congress, obliged to the landlords for electoral support in rural India, was unwilling to implement comprehensive land reforms. Thus, a US government-promoted green revolution, comprising subsidised fertilisers and modern irrigation, new varieties of rice and wheat, hybrids and plant breeding, was favored by India to boost foodgrain production.

Problems of plenty

But this green revolution – essentially the promotion of capital-intensive industrial agriculture – while holding out the promise of provisioning the vast impoverished population with subsidised foodgrain for the government to win over landowning farmers, created its own set of problems. Given the expense, it was rolled out in a few well-endowed states. As bumper grain productions predictably depress prices, farmers were guaranteed procurement through state-run market yards (mandis) at MSPs declared in advance. Thus state procurement transformed Punjab and Haryana into India’s food basket.

However, in the longer term, even the geographically limited package proved fiscally burdensome for the government. As state support began to decline, the problem of remunerative prices and farm debt increased. So did ecological crises – depleting groundwater levels, saline and degraded soils, and biodiversity loss and health disorders due to pesticide use – culminating in a full-blown agrarian crisis and an epidemic of farmer suicides. While the green revolution ensured cheap foodgrain and cereals, it also created a broad base of discontent among the vast majority of farmers and agriculture labourers, who suffered declines in incomes. The result: massive rural distress.

Operation Flood

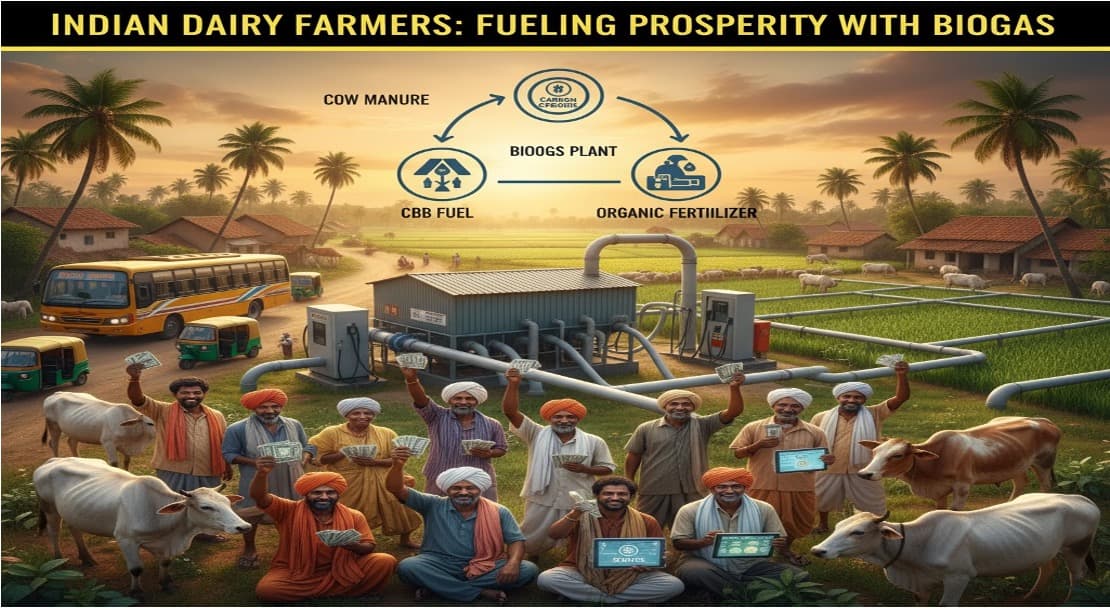

On the other hand, Operation Flood, commonly referred to as the White Revolution, transformed India from a milk-deficient country to the largest milk producer between 1970s and 1990s. It helped dairy farming become India’s largest self-sustaining industry and also India’s largest rural employment provider. It was a success because the bedrock of the “billion-litre idea” was village milk producers’ cooperatives. The cooperatives not only procured milk but also provided inputs and services, making modern management and technology available to their members.

Operation Flood helped dairy farmers direct their own development, by empowering them with the controls of the resources that they create. The cardinal principle on which the operation worked was that the entire value chain – from procurement to marketing – should be the sole and exclusive domain of the farmer, with the small, marginal and landless farmers getting greater importance.

How to end farmer’s distress

The green revolution was focused on making India self-sufficient in food, but today the question is: How to end farm distress and increase farmers’ income. Though the government has been waxing eloquent about ‘empowering farmers’ and the ‘freedom’ they have to negotiate with the traders under the three farm laws, in reality, the laws lay down a litany of procedures and conditions that farmers must fulfill while entering into agreements with large businesses and have been designed without keeping in mind the vastly unequal bargaining powers between the poor farmers and large businesses. Farmers allege that the farm reforms are instruments to hand over regulatory control of agriculture to traders and large businesses.Many supporters of the government have described the controversial farm laws as a major step towards a free market in agriculture. The government has also contributed to this narrative by emphasising that the laws would allow farmers to ‘freely’ negotiate the best deals with large traders and agri-businesses. But the problem with this narrative is that in reality, the farm laws, according to some experts, intrude upon the regulatory powers of state governments and intensify the already severe power asymmetry between corporate businesses and the mass of Indian farmers, nearly 86 per cent of whom cultivate less than two hectares. Some agriculture experts are also of the view that no amount of tinkering at the marketing end will fix a fundamentally warped and unsustainable production model.

Source : Freepress journal Feb 16 2021 by ALI Chougule