Can new age dairy disruptors outsmart India’s famed milk cooperatives?

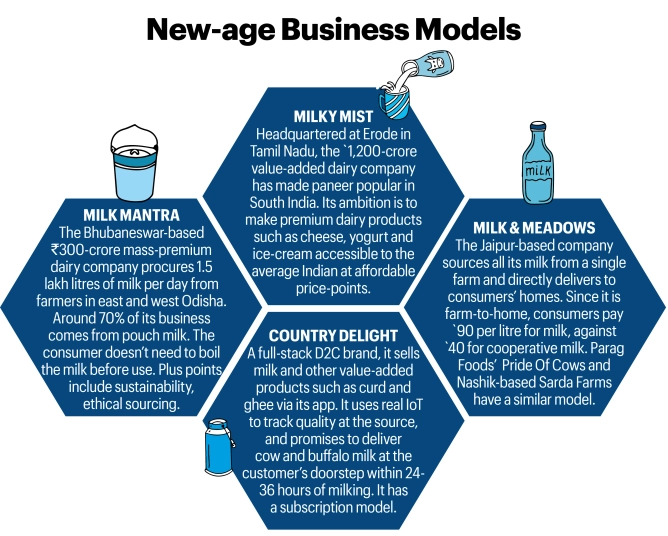

Minati Patnaik, a 55-year-old homemaker in Bhubaneswar had been buying milk from a local milkman for over three decades. Though the latter was infamous for adulterating the milk, Minati chose to ignore it as she had heard worse stories of adulteration by local milk co-operatives. It’s been five years since Minati switched allegiance to Milky Moo (owned by dairy start-up Milk Mantra). The value-conscious homemaker is now happy to pay even a ₹5 premium per litre for the milk.

“The milk is better than the doodhwala’s milk I bought for ages. The best part is I don’t have to boil it. I have even started buying milk and paneer via their Daily Moo app,” says Minati.

For all those who believe Tier-II and III cities shy away from anything remotely premium, Minati is an example. Odisha, in fact, has dozens of consumers who have embraced Milky Moo. The decade-old firm has a 20% market share (despite selling its milk at a premium of ₹5) in the state, says the CEO of one of India’s biggest milk co-operatives. Though local dairy co-operative OMFED has a 50% market share, it is losing clout to private dairies like Milk Mantra and Pragati.

“When we launched in 2012, we were told that we needed to be priced lower than the cooperative, otherwise we will not be able to sell. We took a contrarian view. Since the brand was positioned at a mass premium, the packaging looked and felt different, and stood for itself. The consumer could see the quality of milk was different,” says Srikumar Misra, founder and chairman, Milk Mantra.

Misra and wife Rashima gave up their cushy jobs in London to create a framework of economic inclusion for farmers. On the consumer front, the idea was to bridge the trust gap that existed by offering a high-quality mass premium brand of milk and value-added milk products.

In Tamil Nadu’s Erode, yet another private dairy brand, Milky Mist, has made paneer popular. Paneer was alien to the average South Indian until founder and MD of the ₹1,200-crore dairy company, T. Sathishkumar, introduced it in 1993 by selling 5-10 kgs to restaurants in Bengaluru.

“I launched packaged paneer before Amul launched it nationally,” says Sathish. However, it is only since 2017 that the company scaled up its operations by setting up a fully automated facility in Erode. Milky Mist is a 100% value-added products company and Sathish wants to offer cheese, ice-cream, yogurts and milkshakes to the average Indians as well at a mass price.

Image : Sanjay Rawat

Like Milk Mantra and Milky Mist, there are a host of private dairy companies such as Gyan Dairy (Lucknow), Sarda Farms (Nashik), Milk & Meadows (Jaipur), Country Delight (Gurugram) and Epigamia (Mumbai), which are trying to make a mark in the ₹1,80,000-crore Indian dairy industry with differentiated business models and go-to-market strategies. Not only are they giving the local dairy cooperatives a run for their money, even deep-pocketed private companies such as Nestle and Britannia have not managed to create the wide portfolio of value-added products like these new-age companies. Nestle, whose dairy business in India is over a century old, has a strong presence only in condensed milk and UHT milk.

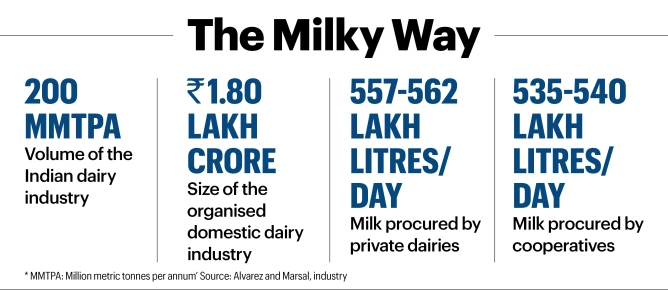

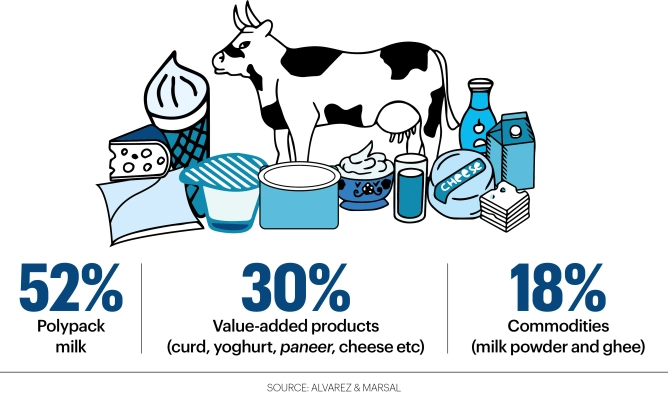

Similarly, Britannia’s focus is largely cheese and butter. Unlike these newage companies which have invested in setting up their milk procurement as well as manufacturing, Britannia continues to contract-manufacture bulk of its dairy products. Private dairies constitute 48-50% of the dairy industry by volume, according to Alvarez and Marsal. “In fact, all the private dairies put together are procuring more milk today than the cooperatives,” points out Rahul Kumar, CEO, Lactalis India. The cooperatives, according to Kumar, procure between 535-540 lakh litres per day, as opposed to the private dairies which procure 557-562 lakh litres per day. “While the likes of Amul and Nandhini (in Karnataka) are far ahead in terms of milk procurement, other state cooperatives (such as Punjab, UP and many others) don’t procure much milk,” Kumar further explains.

While Milky Mist, Milk Mantra and Gyan Dairy are among the early movers, the likes of Epigamia, Country Delight and Sarda Farms are less than a decade old. But each of them is niche. Milky Mist is a market leader in paneer in the South, while Milk Mantra and Gyan Dairy have a 20% share of the dairy markets in Odisha and East U.P.

So, what makes them new-age? Unlike traditional dairy cooperatives which largely sell packaged milk (barring Amul and Nandini), these companies’ portfolio comprises premium milk and value-added products ranging from paneer, cheese, ghee, yogurts, milk shakes and traditional mithais. Companies such as Milky Mist and Epigamia make only valued-added dairy products, while 20-30% of Milk Mantra and Gyan Dairy’s revenues come from such products. Nashik-based Sarda Farms and Milk & Meadows in Jaipur, on the other hand, have a farm-to-home model, wherein the milk is sourced from a single farm and delivered to people’s homes within six-seven hours of milking.

Technologically Speaking

One thing common to all these companies is their dependence on technology.

While Milky Mist has invested ₹550 crore in a fully automated robotic paneer and cheese facility, Milk Mantra has built a technology stack both at the back and front end. Technology not just helps the company ensure transparency at the point of milk procurement and packaging, its D2C app, Daily Moo, is being lapped up by consumers as well. Launched towards the end of 2020, Daily Moo has 10,000 subscribers in Bhubaneswar and Kolkata. Similarly, Lucknow-based Gyan Dairy is betting heavily on its fully automated khoya manufacturing facility, and aggressively pushing its recently launched D2C app. It already has 26,000 subscribers in Lucknow and Kanpur, and is in the process of creating an omni-channel play by combining its 70-odd milk parlours.

“We are betting big on D2C. It enables us to track customer habits and do targeted marketing,” says Jai Agarwal, managing director, Gyan Dairy.

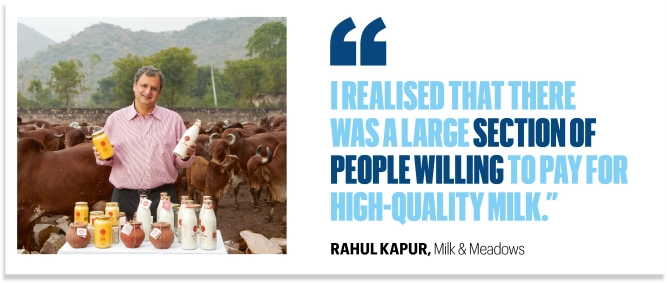

On the other hand, the likes of Country Delight, Sarda Farms and Milk & Meadows are out-and-out tech-based D2C platforms. Country Delight, for instance, uses real-time IoT technology to track quality right at the source. “I realised there was a large section of people willing to pay for high-quality milk,” says Rahul Kapur, founder, Milk and Meadows.

In addition to these homegrown private dairy companies, there are companies such as Godrej, Britannia and ITC, which have made considerable investments. While Godrej Agrovet acquired Hyderabad-headquartered Creamline Dairy, French dairy major Lactalis bought Chennai-headquartered Tirumala Dairy, Prabhat Dairy in Maharashtra and Anik in Indore to set up its India operation. These companies have also focused on value-added products. “We are focusing a lot more on value-added products to grab market share,” says Kumar of Lactalis India.

So, what makes them new-age? Unlike traditional dairy cooperatives which largely sell packaged milk (barring Amul and Nandini), these companies’ portfolio comprises premium milk and value-added products ranging from paneer, cheese, ghee, yogurts, milk shakes and traditional mithais. Companies such as Milky Mist and Epigamia make only valued-added dairy products, while 20-30% of Milk Mantra and Gyan Dairy’s revenues come from such products. Nashik-based Sarda Farms and Milk & Meadows in Jaipur, on the other hand, have a farm-to-home model, wherein the milk is sourced from a single farm and delivered to people’s homes within six-seven hours of milking.

Technologically Speaking

One thing common to all these companies is their dependence on technology.

While Milky Mist has invested ₹550 crore in a fully automated robotic paneer and cheese facility, Milk Mantra has built a technology stack both at the back and front end. Technology not just helps the company ensure transparency at the point of milk procurement and packaging, its D2C app, Daily Moo, is being lapped up by consumers as well. Launched towards the end of 2020, Daily Moo has 10,000 subscribers in Bhubaneswar and Kolkata. Similarly, Lucknow-based Gyan Dairy is betting heavily on its fully automated khoya manufacturing facility, and aggressively pushing its recently launched D2C app. It already has 26,000 subscribers in Lucknow and Kanpur, and is in the process of creating an omni-channel play by combining its 70-odd milk parlours.

“We are betting big on D2C. It enables us to track customer habits and do targeted marketing,” says Jai Agarwal, managing director, Gyan Dairy.

On the other hand, the likes of Country Delight, Sarda Farms and Milk & Meadows are out-and-out tech-based D2C platforms. Country Delight, for instance, uses real-time IoT technology to track quality right at the source. “I realised there was a large section of people willing to pay for high-quality milk,” says Rahul Kapur, founder, Milk and Meadows.

In addition to these homegrown private dairy companies, there are companies such as Godrej, Britannia and ITC, which have made considerable investments. While Godrej Agrovet acquired Hyderabad-headquartered Creamline Dairy, French dairy major Lactalis bought Chennai-headquartered Tirumala Dairy, Prabhat Dairy in Maharashtra and Anik in Indore to set up its India operation. These companies have also focused on value-added products. “We are focusing a lot more on value-added products to grab market share,” says Kumar of Lactalis India.

The challenge is that setting up a milk procurement operation at the scale of cooperatives is time and effort intensive. Moreover, some governments and dairy cooperatives dole out generous subsidies to farmers, making it difficult for private players to compete. “Cooperatives have multiple objectives and in most cases are not primarily profit oriented,” explains FMCG veteran Venkat Shankar, and founder and partner, ExQ, a Chennai-headquartered consulting firm. New-age dairies have to match the prices of cooperatives, but end up procuring less quantity since the process is expensive. To make this a sustainable play, companies are investing in weaving a narrative around their brand, and by doing so, are able to charge a premium from consumers.

Milk Mantra, for instance, has built its proposition around sustainable and ethical sourcing. The company has removed intermediaries from the value chain and pays farmers directly. “We pay ₹2 more than the local cooperative and make sure that the farmer actually gets the premium. Because of our tech dependence, we were able to change the payment dynamics. We pay directly to the farmer and that too in five days, unlike the cooperative, which pays in 10 days,” points out Misra.

On the consumer front, the strategy has been to offer functional dairy products. The company has invested in technology which not just increases the shelf life of the milk it sells, but also comes with a promise that the milk needn’t be boiled before consumption. These value-adds obviously come at a premium. “If you position a brand at a 30-40% premium, the addressable market falls off the cliff. We said we will be at 20% premium, which will address 80% of the market. We will lose 20%, but we will be able to have mass premium positioned brands that will address our financial metrics,” adds Misra.

A superior-quality product is the focus of Milky Mist’s Sathish too. He has invested ₹550 crore in setting up fully automated, robotic plants to manufacture paneer, cheese and other value-added products. He is investing another ₹900 crore to foray into categories such as ice-cream and Greek yogurt. The aim is to service at least 50-60 lakh outlets (they currently do 3.5 lakh).

In order to keep a tab on quality, Milky Mist, like its counterpart in the East, not just has complete control over its backend, it also owns the supply chain. “We own 130 trucks and have installed 15,000 chillers in the market. Since the cold chain in the kirana stores is of poor quality, we can’t sell unless we give them chillers.”

Does owning the fleet make good business sense? It has proved to be an expensive proposition for the likes of Danone and others. “If I don’t own my fleet, there is no way I can control quality. There are stories of truck drivers switching off chillers en route to the market,” explains Sathish.

Almost 40-45% of Lucknow-headquartered Gyan Dairy’s revenue comes from commodities such as skimmed milk powder, ghee and butter. The dairy promises superior quality and has been able to maintain a premium. It is now investing in a fully automated khoya plant, and has created a two-pronged strategy of catering to institutions with high-quality commodity products as well as a consumer strategy of selling value-added products via its milk parlours and D2C app. Such products currently contribute 20% to the revenue of the ₹1,000-crore company and the plan is to scale up to 30%.

Value-added is where the margins come from. Almost 20% of Milk Mantra’s revenue comes from its portfolio which includes paneer, milkshakes, yogurt and traditional Odia sweets. It also sells differentiated products such as paneer sandwiches, cakes and muffins, along with its regular portfolio of milk and other products, on its Daily Moo app. “In five-seven years, D2C will be a 20-25% play for us. It is below 5% now, but growing,” says Misra.

Premium Dairy

While the likes of Milk Mantra, Milky Mist and Gyan are playing in the mass to mass-premium category, brands such as Country Delight, Milk and Meadows, Sarda Farms and Epigamia charge a substantial premium. Milk and Meadows, for instance, procures 650 litres of milk daily from its farm and supplies in Jaipur at ₹90 per litre. The milk supplied by the local cooperative is priced at ₹45. Kapur promises high-quality A2 Gir milk (supposed to be easier to digest and healthier than the normal A1 milk as it lacks a kind of protein called beta-caesin considered to be unhealthy). “There are no middlemen involved. I have my own trucks, which deliver right at the consumer’s doorstep,” he says.

Sarda Farms and Parag Foods’ Pride of Cows also have a similar model. All the milk is sourced from a single farm, the process is completely automated, and hence the premium. Country Delight, on the other hand, procures milk from farmers but by virtue of its commitment of offering pure cow or buffalo milk has priced its product between ₹70- 80 per litre.

Since Pride Of Cows is part of a larger dairy play, Parag Foods, it is profitable. However, experts aren’t sure if niche models such as Milk and Meadows or even Country Delight make money. Since they are tech-based and promise to solve trust deficits, they do have private equity backing. ““It will be difficult for them to make money since they don’t have a procurement advantage. They are procuring at a premium since they don’t have scale,” explains Shankar of ExQ. And it will be increasingly difficult for most newage dairies to build scale. “Cooperatives left some obvious gaps in the marketplace and business models. Early movers such as Parag, Tirumala and Hatsun have plugged into those gaps. For someone new to set up a full dairy play, the capital investment is significant. The sourcing network is also challenging. Add to this brand building costs and the challenges just keep multiplying,” adds Shankar.

Rishav Jain, MD, lead, consusmer, consumer tech, retail and agri business, Alvarez and Marsal, believes these D2C milk-tech companies could build sizable business among SEC-A consumers, which comprise 14-16% of the population in the top 10 cities. This is the segment which is willing to spend more on nutritional products. “If you are selling milk at ₹65-80 per litre, you can garner an annual topline of ₹240-290 crore for every lakh litre sold per day. In the top eight cities, the polypack milk market is close to 200-250 lakh litres a day. Every 100 basis points of market share can result in a topline of ₹500–650 crore depending on the pricing (₹65-80 per litre),” Jain calculates.

He also agrees that regular poly-pack milk has low gross margins but D2C players operate at healthy milk gross margins. “However, the larger consumer base is still with cooperatives and private dairies who are selling poly-pack milk.”

The other premium business model is that of Drum Foods, which makes value-added products such as Greek yogurt, smoothies and milkshakes under the Epigamia brand. Since procuring milk isn’t the company’s core competence, it works with co-packers such as Schreiber Dynamix from where they source milk. “Milk is a key ingredient for our products, and we have put in place stringent quality standards. But we are a FMCG brand, not a dairy company,” says Rohan Mirchandani, co-founder, Epigamia. “Dairy for us is an ingredient as much as the fruit — the mango or the banana — that goes into our yogurts or smoothies.”

Even the likes of Britannia have built their dairy business on the back of co-packers. But will it sustain in the long-term? “When you co-pack you don’t control the milk and that’s when problems begin. Your costs go up and margins shrink,” says Shankar.

The milk business is successful only when one has command over procurement, says Kumar of Lactalis India. “Almost 75-80% of a value-added product’s price is raw material cost. You have to command procurement not just in terms of rate but also quality. You have to build a relationship with your farmer so that you control the milk you procure. Only then will you get economies of scale and you can launch better products.”

Regional Play

Dairy cooperatives’ shares may be dipping across the country, but they are extremely strong. Trust levels are very high as they have been delivering milk in the morning since decades. Also, their model of selling milk is profitable, working capital needs are very low, there is no long inventory and no distribution system that is going to take credit. All the milk that they produce gets converted into cash almost instantly. Even if margins are low, it’s a good return on capital business.

In fact, none of the private players have been able to build a large liquid milk business because of the cooperatives. While Amul and Mother Dairy are exceptions, most of the others have stuck to states they belong to. Reason: When one is into fresh dairy, one needs to procure fresh and sell fresh. Most of the new-age dairy companies prefer to stay regional at least for the medium term. “We have taken a conscious call to be regionally focused in the medium term, to become a ₹1,000-crore company in the East itself (currently ₹300 crore). We want to remain in the East at least for the next four-five years and then probably look at replicating the model sustainably across other parts,” says Milk Mantra’s Misra.

Though Milky Mist has started distributing its value-added products nationally, Sathish has no plans to set up procurement or manufacturing outside of Tamil Nadu. “We will look at plants in the North and West at a later stage,” he says.

Milk Mantra, however, plans to distribute its long shelf life value-added products nationally. And that’s been the strategy of most private companies, including the likes of Godrej and Lactalis India. “The business is so large in one territory that you need to maximise in that territory before rushing to another state. However, with the long shelf-life products we have gone national,” says Bhupendra Suri, CEO, Godrej Jersey. Lactalis India also sells President Butter, its antibiotic-free UHT milk and Lactel yogurt in modern stores across the country.

While new-age dairy companies are still scaling up, they are beginning to polarise the industry at the premium end with the introduction of innovative products, along with premium milk. Hence, they command a lion’s share in the premium segment, while most of the mass-premium mass segment is dominated by cooperatives and traditional private players,” says Jain of Alvarez and Marsal.

So, will these companies grow at the expense of cooperatives? Not really, the cooperatives are established household brands, and will continue to be so.

The tussle between cooperatives and private dairies, meanwhile, continues.