A big fat problem in milk: What’s driving up prices?

The current price inflation in milk is mainly due to a shortage of fat. It has led dairies to hike full-cream milk prices or to cut fat content through rebranding of existing products. Also, milk does not attract GST, while fat and powder used in reconstitution does, an anomalous situation for which the consumer ultimately pays.

Till mid-October last year, GCMMF was charging consumers Rs 10 per litre more for full-cream milk compared to toned milk. The maximum retail price (MRP) for its ‘Gold’ full-cream milk, containing 6% fat and 9% SNF (solids-not-fat), was Rs 62 per litre in Delhi, as against Rs 52 for ‘Taaza’ toned milk with 3% fat and 8.5% SNF.

But since then, the price difference has gone up to Rs 12, with the MRP of Gold raised to Rs 66, and of Taaza to Rs 54 per litre.

The Karnataka Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation, India’s second-largest dairy concern, has done the same for its Nandini milk. While regular pasteurized toned milk is retailing at just Rs 39 per litre, the MRP for the ‘Samrudhi’ full-cream variant was Rs 50/litre before being increased in a roundabout way in early March. Consumers are still paying Rs 50, but only for 900 ml, which translates into an effective MRP of Rs 55.56 a litre. The price difference vis-à-vis toned milk has widened from Rs 11 to Rs 16.56/litre.

The Tamil Nadu Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation (Aavin) has, likewise, raised the MRP of its ‘Premium’ full-cream milk in Chennai from Rs 48 to Rs 60 per litre with effect from November 4. The MRPs of toned and standardized milk (with intermediate 4.5% fat and 8.5% SNF content) have been kept unchanged at Rs 40 and Rs 44 per litre respectively. However, in some markets such as Madurai, Tirunelveli and Coimbatore, Aavin has replaced sales of standardized milk with so-called ‘cow milk’, having 3.5% fat and 8.5% SNF.

It’s about fat

The current price inflation in milk has mainly to do with a shortage of fat. It has led dairies to increase full-cream milk prices more or to cut down fat content through rebranding of existing products. There have even been reports of branded ghee and butter disappearing from store shelves.R S Sodhi, president of the Indian Dairy Association, links this partly to the falling contribution of buffaloes to national milk production. The share of buffaloes — their milk has an average 7% fat and 9% SNF content, against 3.5% and 8.5% of cows — to total output was about 46.4% in 2021-22. In 2000-01, it stood at 56.9%, even as the share of crossbred/exotic cows has risen (18.5% to 32.8%) and that of indigenous/non-descript cattle declined (24.6% to 20.8%) over this period.

“Demand is growing for ghee, ice-cream, khoa, paneer, cheese, and other high-fat milk products. But supply is coming more from crossbreds that give low-fat milk. The mismatch is pushing fat prices higher,” explained Sodhi. Even tea shops prefer buffalo milk. This milk, with 15-16% total solids, can be diluted to serve more cups and creamier tea.

Export-induced inflation

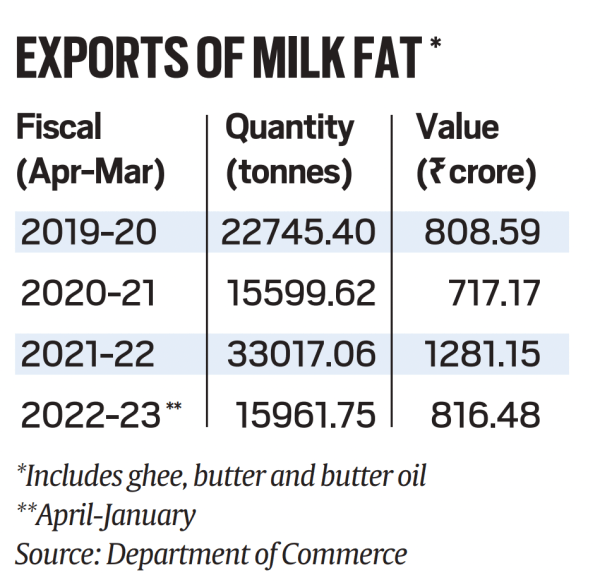

However, a more immediate reason for rising fat prices is exports. During 2021-22, India exported over 33,000 tonnes of ghee, butter, and anhydrous milk fat valued at Rs 1,281 crore.Increased exports (see table) came at a time when milk production was taking a hit from farmers underfeeding their animals and shrinking herd sizes — due to low prices received during the Covid lockdowns, escalation in fodder and livestock feed costs, and lumpy skin disease outbreak among cattle. Exports of milk fat table.

Exports of milk fat table.

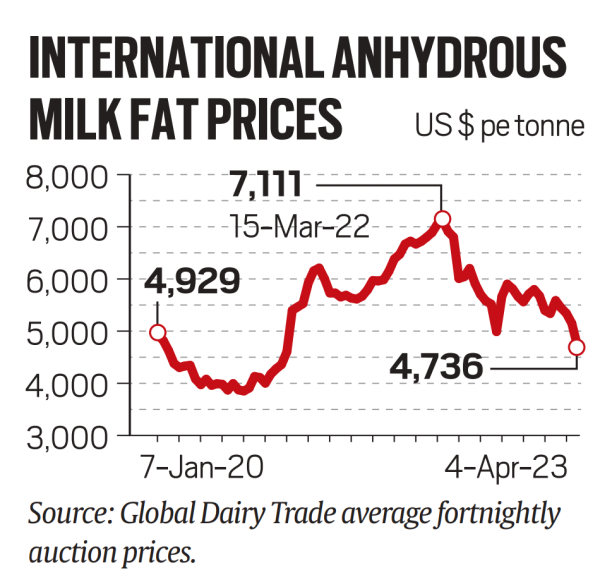

The supply-side pressures built up just when demand was returning with the lifting of lockdown restrictions and resumption of economic activity. Exports — enabled by global fat prices skyrocketing from $3,850 per tonne in September 2020 to a record $7,111 in mid-March 2022 (see chart) — added fuel to the fire, exacerbating domestic shortages.

International milk prices chart.

International milk prices chart.

Ex-factory prices of yellow (cow) and white (buffalo) butter crashed to Rs 225-275 per kg during the March-July 2020 demand destruction period. From those lows, they had soared to Rs 420-430/kg by February-March this year. “Prices have since eased to Rs 400-405 for white and Rs 410-415/kg for yellow butter, following reports of the government planning to lower the import duty on milk fat (from 40%),” said Ganesan Palaniappan, a Chennai-based dairy commodities trader.

On Friday though, Union Animal Husbandry and Dairying Minister Parshottam Rupala dismissed any such move. Imports have become viable with global fat prices, too, dropping below $4,750 per tonne.

Alternative to imports

With imports ruled out — high prices, it is believed, will incentivize farmers to invest more in their animals and ramp up production — can there be an alternative solution?October-March is normally the ‘flush’ season in milk, when supply exceeds demand. Dairies convert the surplus that they procure into skim milk powder (SMP) and butter fat. This is done by separating the cream and removing the water in the skimmed milk through evaporation and spray drying. The same SMP and fat is reconstituted into whole milk during the ‘lean’ summer-monsoon months (April-September), when animals produce less amid rising demand for curd, lassi and ice-cream. Such processing into solids and reconstitution by adding water happens in no other farm produce: atta flour and sausages once made cannot be turned back into wheat or pigs.

The 2022-23 ‘flush’ was a rare season where milk procurement fell, leaving dairies with hardly any surplus for converting into fat and powder. And with production bound to fall further in the ongoing ‘lean’, the dependence on purchase of milk solids for reconstitution will only go up.

Fixing GST anomaly

Therein lies a problem. Milk doesn’t attract any goods and services tax. But SMP is taxed at 5% and milk fat at 12%. So while dairies pay no tax on milk procured from farmers, they have to shell out GST on solids. And input tax credit cannot be claimed, as there’s no GST on milk itself. Moreover, the tax incidence goes up as the fat in the reconstituted milk increases.For every 100 litres (103 kg) of full-cream milk that dairies process, 6.18 kg of fat and 9.27 kg of SMP is produced. Butter contains 82% fat. Taking its price at Rs 425/kg (Rs 518/kg of fat) and SMP’s at Rs 325/kg, their combined cost in the reconstitution of 100 litres will be Rs 6,214. Adding 12% GST on fat and 5% on SMP takes it to Rs 6,749 or Rs 67.49 per litre.

Simply put, the total cost of fat and SMP used in reconstitution of one litre of full-cream milk is today around Rs 67.5. The GST component in that is Rs 5.35/litre — Rs 3.84 on fat and Rs 1.51 on SMP — which is ultimately passed on to the consumer.

One way to avoid this is by doing away with GST on milk solids used for reconstitution purposes. Alternatively, the GST on milk fats can be reduced to 5%. Differential rates on SMP and fat probably make no sense, when both are derived directly from milk. A 12% GST on milk fat is also an anomaly when vegetable fat (edible oils) is taxed at 5%.