An old but interesting article

On World Vegan Day this year, the Internet was rife with a list of celebrities who have adopted a life free of animal products. The names included actors Aamir Khan and Sonam Kapoor, and cricketer Virat Kohli. Then there are premium magazines that fill in readers about elaborate vegan diet plans of India’s biggest celebrities. Against this backdrop, the country’s food regulator put out draft guidelines on classifying vegan-packaged foods in September this year, along with a new logo for them.

These were signs enough to indicate that though small, vegan foods as a consumer category were gaining plenty of traction in India. However, it’s not often that a new consumer segment attracts attention from the courts.

Plant-based vegan alternatives for milk have become the talk of the industry, with a Delhi High Court case pitting these vegan brands against the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI).

India’s market for plant alternatives for milk and meat is pretty small — some estimates put milk alternatives at between INR200 crore and INR230 crore to up to INR300 crore. There aren’t any for meat alternatives. While it is growing rapidly, the growth-rate estimates vary wildly.

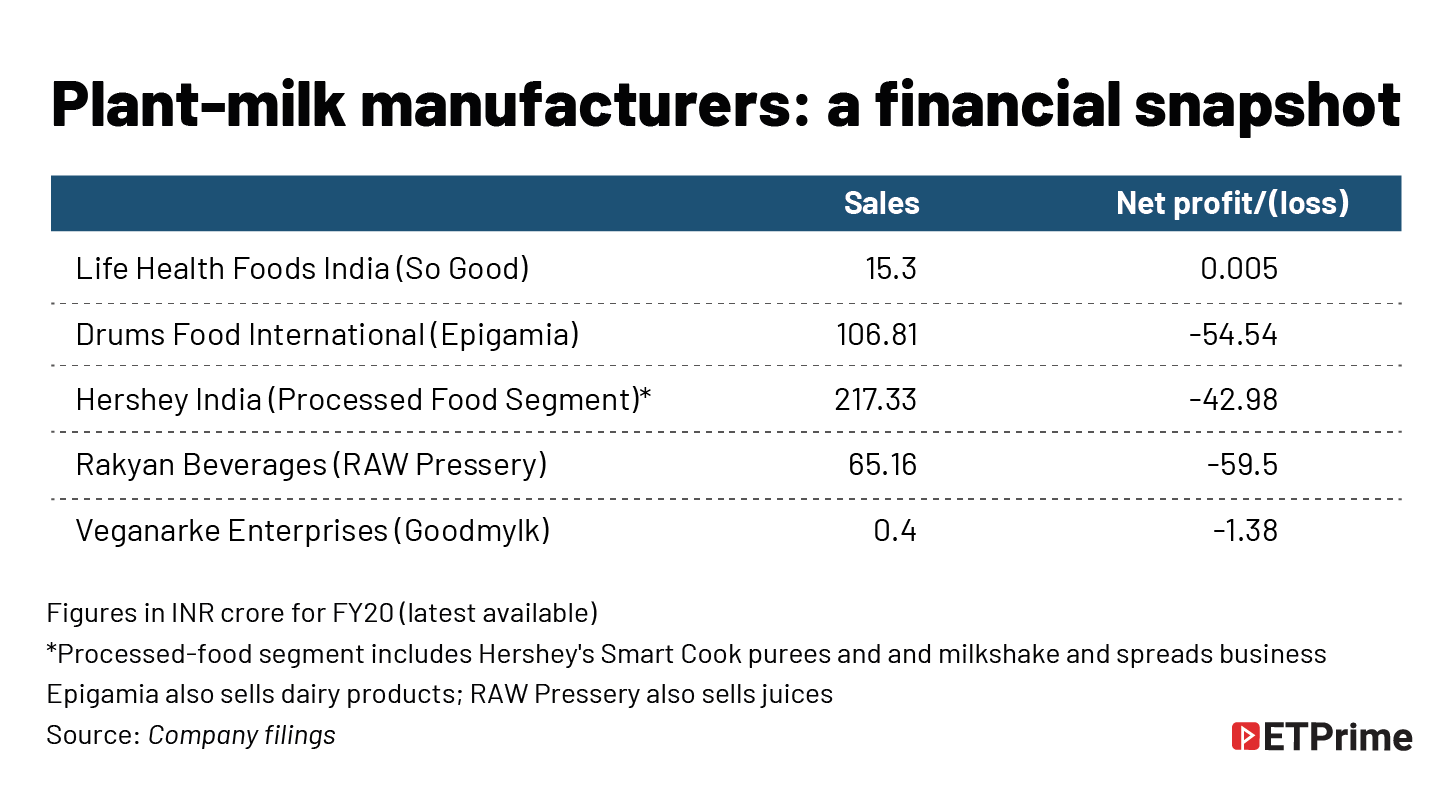

Large foreign brands already have skin in the game. US’s Hershey sells soy and almond milk under the Sofit brand, whereas New Zealand’s Life Health Foods has been selling a variety of plant milk under the So Good brand. French dairy major Danone-backed Epigamia and Sequoia-backed RAW Pressery are also looking to grab a pie of this burgeoning business.

Consumers in European and American markets have been in a long arc towards sustainable consumption, including going vegan. Some of this is a move to counter the non-ethical and polluting practices of industrialised dairy and meat production, particularly in countries of Europe and North America.

A large chunk of vegans is turning away from animal-product diet due to a growing belief in ‘clean’ eating that eliminates lactose (present in dairy) and meat because it is believed by many to harm their health (although the scientific evidence on this is not conclusive).

“This is a very good, very loyal, and a slightly premium market (plant-based products). You don’t want to be in a place where you are in every home and playing a price war.”

— Chirag Kenia, founder and managing partner, Urban PlatterSome of these consumer trends are now prevalent among richer, urban consumers where lifestyle disorders — cardiovascular diseases, hormonal and reproduction issues — are common. Studies have conclude that between 60% and 75% Indians are likely lactose-sensitive or intolerant, meaning they cannot digest lactose present in cow’s milk completely.

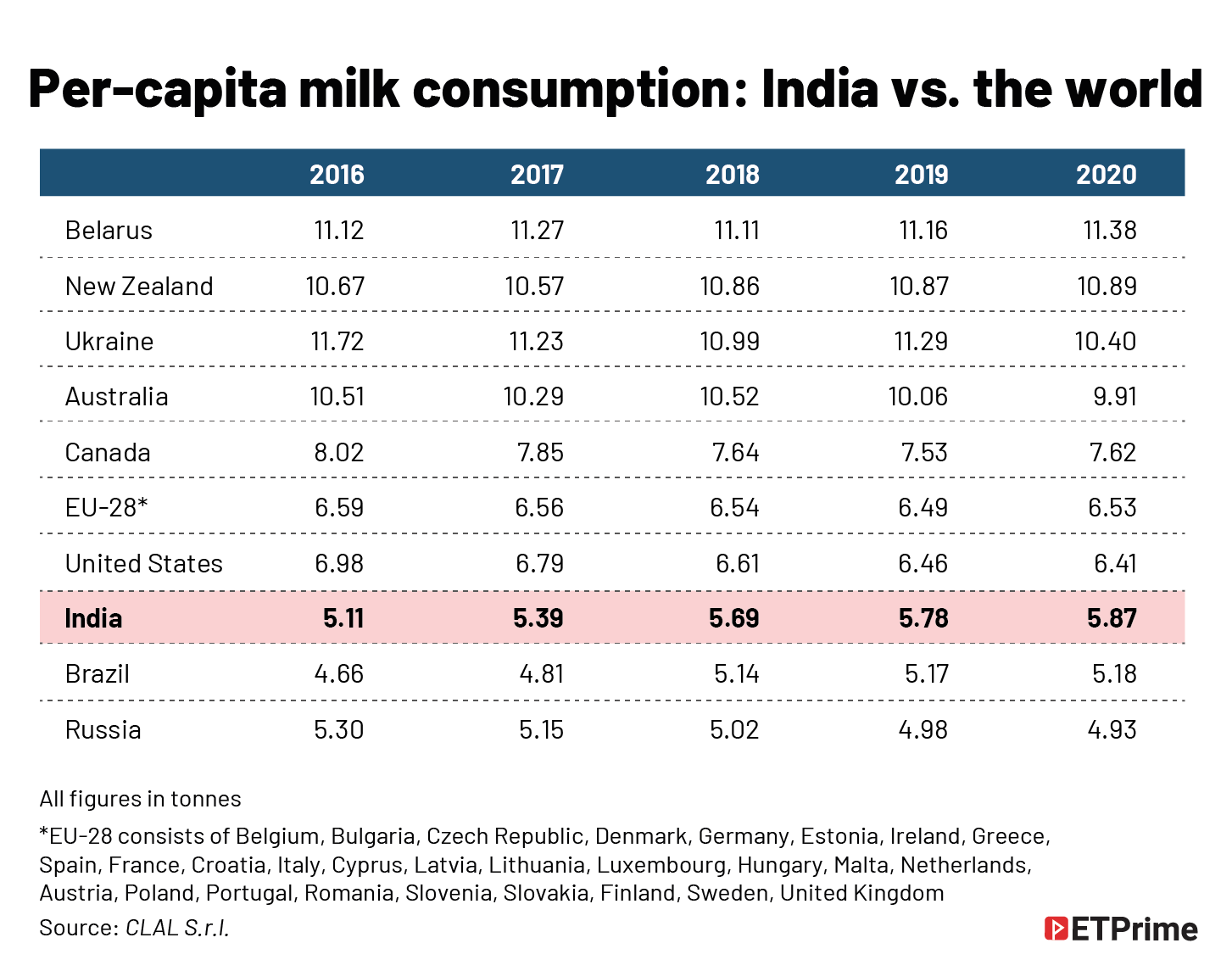

Ethical concerns are also driving affluent urban consumers to make similar choices as their western counterparts despite India’s per capita consumption of both milk and meat being much lower than that of developed countries.

In FY21, Life Health Foods India reported a 28% jump in sales to INR19.3 crore and went from just break-even to a net profit of about INR29 lakh, according to MCA filings.

An exception is the market for meat alternatives, much smaller in India in comparison to the dairy alternatives. The demand for these is driven by religious and social concerns, although several of these plant-milk manufacturers either already have meat alternatives on offer (Life Health Foods, Urban Platter) or are planning to (Goodmylk). More on that in the second instalment of this story.

“Our management are all former animal-rights activists,” says Abhay Ranga, founder of Bengaluru-based Goodmylk. “The first few thousand customers were largely vegan [as an animal-rights ethical stand]. Now our consumers are largely coming to us for a healthier alternative [to dairy]. I don’t know how many Indians are fully lactose-intolerant, but [this shift among consumers] is more about realising that dairy isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be and there are healthier alternatives out there. It’s the same as [the shift to] olive oil from sunflower oil.”

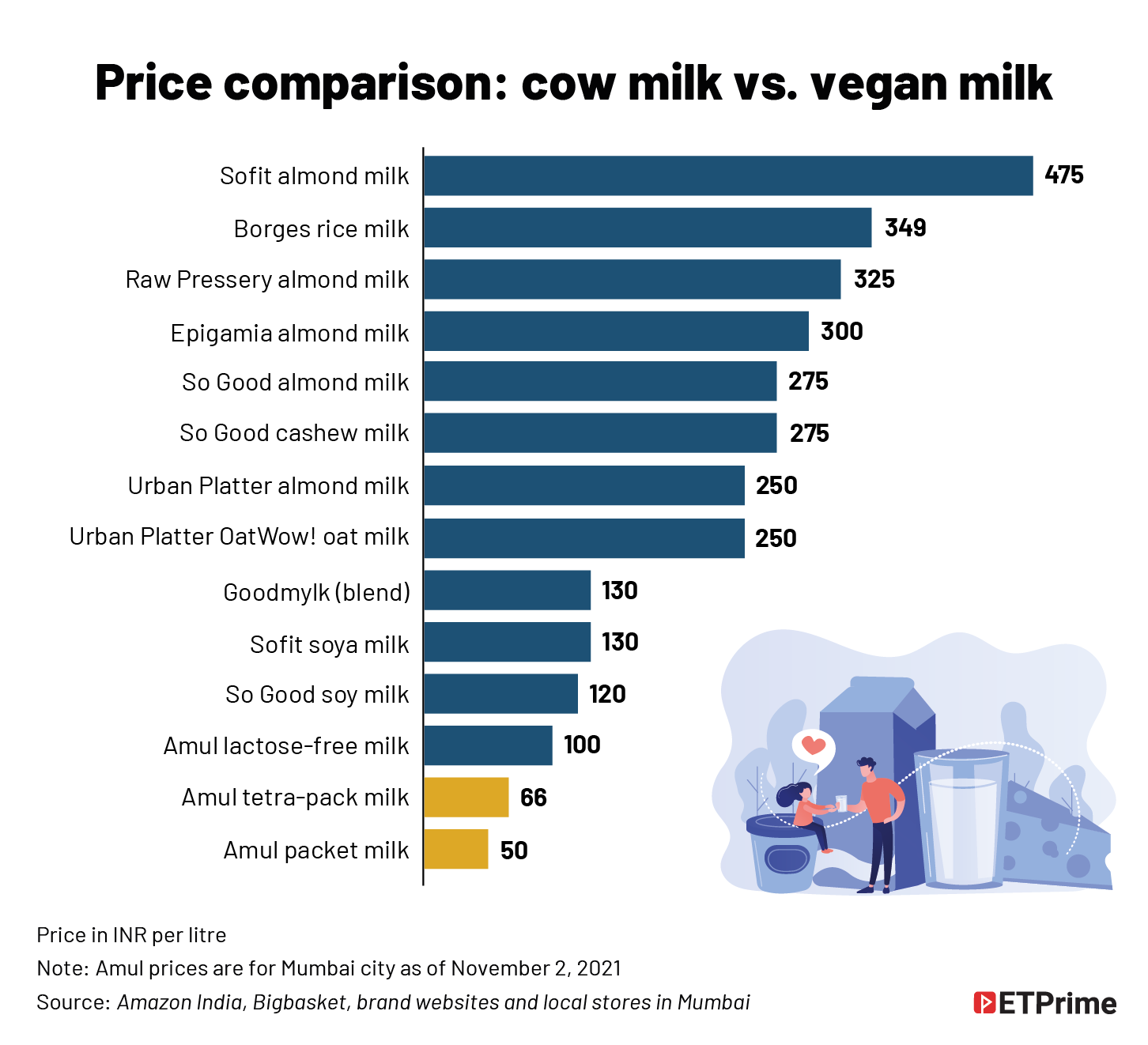

A majority of the plant-milk market is still online, via grocery e-tailers like Bigbasket and Amazon, or direct-to-consumer channels operated by the brands themselves. In India’s largest cities, standalone supermarkets and high-end stores, along with big supermarket chains, are also prime channels for everything from soy milk (present in India since long) to new imported blends like rice and walnut milks. Compared to packaged dairy products, including premium ones like milk in Tetra Pak, these vegan alternatives are significantly more expensive.

Decisions on which kind of plant milk and what brands to buy are still largely influenced by online media. “In India, you have people across the country who are constantly being influenced by various mediums being pushed to put alternatives on their plates,” says Chirag Kenia, founder and managing partner of Urban Platter, an online vegan-foods brand that also sells almond milk and oat milk. “This is playing out on social media, on a medium like WhatsApp, across the health sector. This is an interesting conversation happening across the country”.

So, why are prices for these products so high? Plant ‘milk’ is manufactured using water and relatively expensive ingredients such as almonds, cashew, and soya. Most brands rely on third-party manufacturing for now, but the costs of products like almonds — often imported from California for their good quality — drive up the retail price of the end product. Besides, as demand grows and shifts from soya milk to newer and more expensive alternatives like almond milk, options and prices are rising further in this sub-segment. Almond milk’s rising popularity over soya is because it tastes better and is perceived to be healthier than soy, say founders of vegan milk brands.

“This is a very good, very loyal, and a slightly premium market. You don’t want to be in a place where you are in every home and playing a price war,” Urban Platter’s Kenia says.

An exception to this very premium market is coconut milk, a non-dairy milk that is traditionally used in several cuisines across the country but is not generally marketed as an alternative to cow’s milk. The market for coconut milk is much bigger and mostly geared to homes that need the ingredient for traditional coastal cooking. Large listed firms like Dabur cater to this market.

Why is Big Dairy worried?

The market for plant milk is only just burgeoning, and there is hardly an overlap between packaged dairy consumers and potential consumers of vegan alternatives, because the price differential is gigantic — between 2x and 5x the price of a litre of Tetra Pak cow’s milk, which is anyway considered a premium product in the dairy market.

But the market is burgeoning enough to have caught the attention of India’s Big Dairy — Amul, Mother Dairy, and other national and local milk co-operative brands that dominate India’s dairy market, estimated to be about INR1.5 lakh crore in value.

Dairy brands say they are concerned because they believe plant-based milks are inferior to dairy.

“If you make plant-based products, you have to make sure you say they are synthetic products with some natural ingredients, with artificial colour, flavour,” says RS Sodhi, managing director of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, owner of the Amul brand. “You eat food because of three things — taste, nutrition, and affordability. These products do not meet any of these parameters. They are not natural products. They are nutritionally very inferior [to milk protein]. They are not plant based; they are chemical based. They are artificial”.

Amul ran an ad campaign in the print media in March this year, claiming to bust the myth that the dairy industry is cruel to animals, and to assert that cow’s milk is a natural, complete “superfood”.

But this is no longer a tussle playing out in newspaper advertisements. India’s milk co-operatives are putting pressure on the country’s food-safety regulator for a pushback. And this has moved to the courts.

On September 1, the FSSAI issued a letter to e-commerce food business operators (such as Bigbasket and Amazon) saying it had received a complaint from the National Cooperative Dairy Federation of India, way back in March this year. It seems India’s dairy co-operatives were upset that plant-milk brands were calling themselves ‘milk’.

The letter reminded these brands that under FSSAI rules for milk and milk products, no product that is not specifically of dairy origin can use the “nomenclature of dairy products” except certain goods like coconut milk and peanut butter “based on the internationally accepted principle that dairy terms were being traditionally used in their nomenclature and such products are not substitutes for milk or milk products”.

Essentially, the letter was an order to grocery e-commerce firms — delist any plant alternative for dairy that uses dairy terms in violation of FSSAI definitions. The deadline? “Immediately”, the letter ended.

Right after, parent firms of five brands — Epigamia, RAW Pressery, Goodmylk, Urban Platter, and Hershey India — moved the Delhi High Court against the order. Lawyers for the brands argued that one of them was operating on an FSSAI licence that identified its product as ‘soy milk’.

On September 10, the court passed an order staying FSSAI’s directive, but said the regulator was free to conduct an investigation on the alleged violations. The case is going on and will next be heard in January 2022.

An FSSAI spokesperson did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The legal campaign did affect sales of plant-based milk for a short while, says a senior executive at a leading plant-milk brand, requesting anonymity. Most brands involved in the case were forced to address their supply chain, vendors, and customers, given that almost everyone relies heavily on e-commerce platforms for their revenues. Some such as Life Health Foods’ So Good have changed their nomenclature despite the court’s stay and are calling themselves plant-based beverages, instead of milk.

“No doubt, they should grow and market. But they should have their own segment, and not hijack the terminology of the dairy business. They are misinforming consumers,” Amul’s Sodhi says. “Veganism — this is a fad. What will you do if you don’t have proper nutrition? What will you do if you don’t have proper calcium and protein?” he asks.

Amul is also addressing the market for dairy alternatives to tap consumers unable to digest lactose, estimated to be a bigger cohort than those invested in the ethics of an animal-products-free life.

Amul sells lactose-free cow’s milk in 250ml Tetra Pak for INR100 a litre. While the product is “doing very well in urban markets”, Sodhi declines to share the numbers, saying it is still less than 1% of Amul’s milk sales. At an annual turnover of nearly INR40,000 crore, that is still a formidable figure. Amul also has a lactose-free ice-cream and wants to concentrate on new “health” products. “Lactose-free, sugar-free, there is a big market here,” Sodhi says.

The bottom line

The scale of India’s plant-milk business does not even compare with the behemoth that is India’s packaged-dairy industry. Yet, here it is, embroiled in a legal and regulatory tussle.

Meanwhile, foreign and domestic venture capital is backing the vegan action. It has started with milk; the next frontier is meat alternatives. But that is a smaller market, and the target consumer is more complicated to define. Among those involved in that space is a listed restaurant chain and a Bollywood actor couple. Some of the plant-milk brands are either already selling meat alternatives or have interests in this space. More on that in the next instalment of this story.