Cattle have so far not been associated with being infected on large-scale, and as a result, cattle have not been well studied as domestic hosts for influenza A virus species. In contrast to the notion that cattle are considered to be almost resistant to infection with influenza A virus, H5N1 virus, which was first detected in dairy cattle in Texas in late March, has rapidly spread to 37 herds in nine States in the U.S. as of May 7.

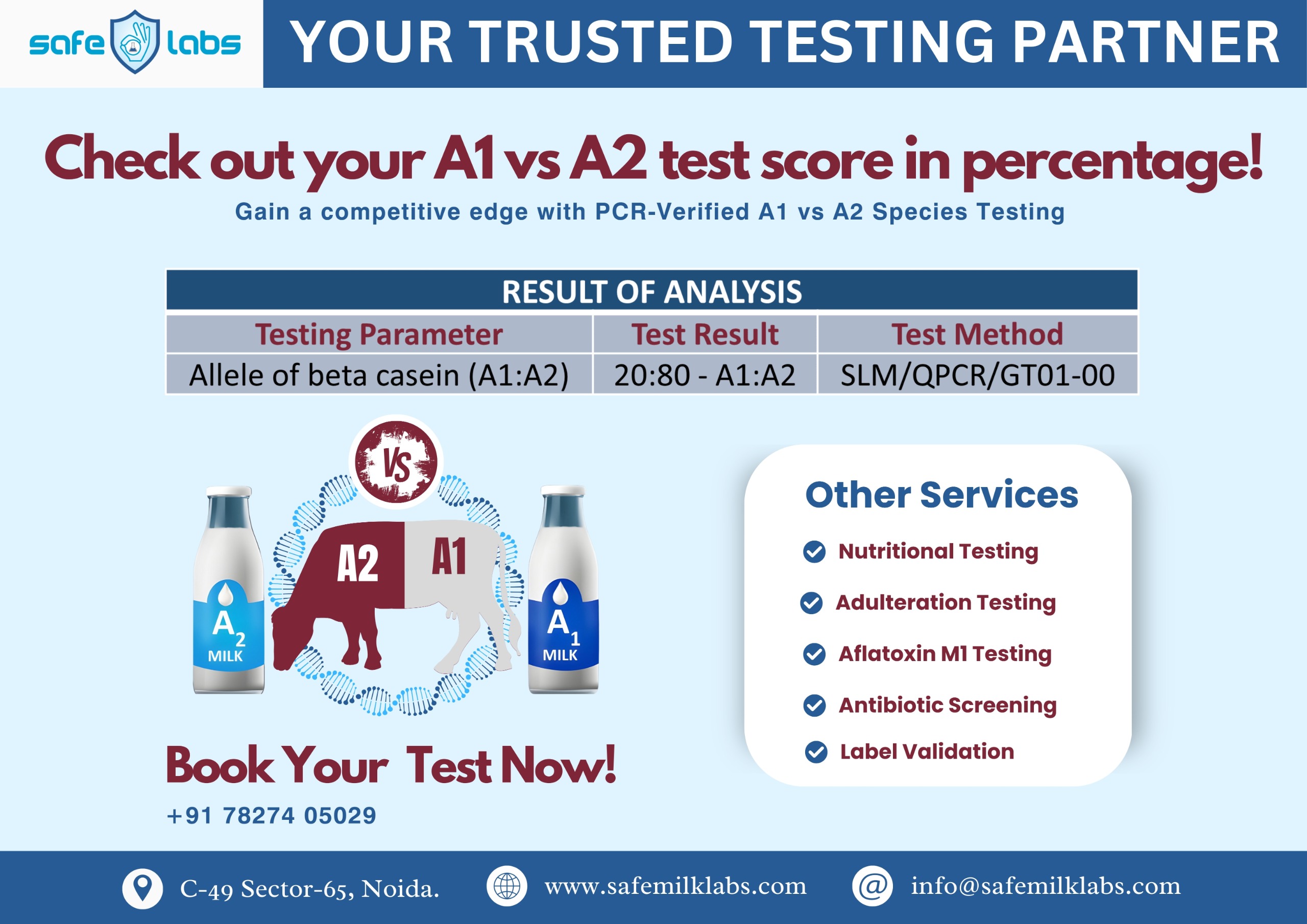

On April 24, the U.S. FDA said that in a nationally representative commercial milk sampling study of pasteurised milk, about one in five of the retail samples tested positive for bird flu viral fragments. A greater proportion of positive results were in milk from areas with infected herds. An NIH-funded study had found an absence of infectious virus in milk samples. The April 23 report of the FAO noted that the H5N1 virus was detected in “high concentrations in milk from infected dairy cattle and at levels greater than that seen in respiratory samples”. That the concentration was less in the respiratory samples of the infected cows compared with the milk samples strongly suggests that the pathogenesis of the H5N1 virus in cattle differs from other mammals, says a study posted as a preprint; preprints are yet to be peer-reviewed.

One reason for dairy cattle milk containing high concentrations of H5N1 virus fragments could be the propensity of the virus to infect the mammary glands of cows as a previous study had found. On evaluating the expression of H5N1 receptors in the mammary gland, respiratory tract and cerebrum of cattle, the authors found both the human and the duck receptors to be highly expressed in the mammary glands. In the mammary gland, the human receptors and the duck receptors were found to be widely distributed in the alveoli but not in the ducts. Chicken-type influenza receptors were common in the cow respiratory tract.The high concentration of H5N1 virus fragments in milk from H5N1-infected cows could be due to local viral replication in the mammary glands of cows as H5N1 has a high affinity for the receptor, the authors say.

The study found that the chicken receptor was expressed on the surface of the respiratory epithelium in the upper respiratory tract and upper part of the lower respiratory tract, while human and duck receptors were either lacking or very limited in expression. However, in the lung alveolar cells, the researchers found all the receptors of humans, chickens and ducks being abundantly expressed.

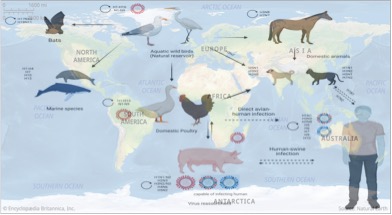

The abundance of human and duck receptors in the mammary glands and the large presence of human, chicken and duck receptors in the lung alveolar cells of cows provides a perfect environment for the evolution of H5N1 viruses that can easily spread from animals to humans. The reason why pigs are called the “evolutionary lab for flu host switching” is precisely due to the presence of both the human-flu and avian-flu host cell receptors in their upper-respiratory tract, says Dr. Sam Scarpino from Northeastern University in a tweet. The latest study has found that cow mammary glands contain the same kind of mixed flu receptors seen in pigs.

“One of the key changes required for avian flu to transmit effectively in humans involves flu’s hemagglutinin (HA) host cell receptor preference,” Dr. Scarpino said in another tweet. “Currently the cell surface receptor that influenza uses in birds is subtly different from the one in the human upper-respiratory tract”. But when pigs get infected with human and avian influenza viruses at the same time, the viruses can potentially undergo reassortment, wherein small segments of their genomes get swapped. The swapping might sometimes help the avian flu viruses to become better adapted to bind to human receptors and hence spread from birds to humans more easily. The H1N1 pandemic of 2009 was due to the reassortment of the virus in pig populations.