Beverages are displayed neatly side-by-side with each other in grocery stores across the country. And while a whole section may say milk, a good chunk of the inventory has no dairy inside.

That “milk” label on a growing variety of plant-based beverages has been on the minds of dairy advocates since the ’70s as they fight the battle to regain ownership of the name, and with it, the market.

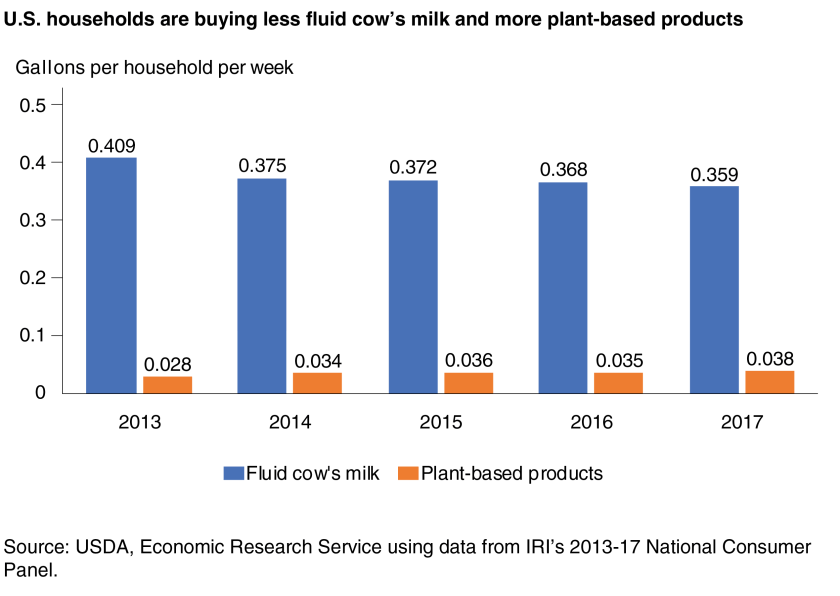

The United States Department of Agriculture claims that fluid milk, the kind that comes mainly from cows, has seen steady decreases in consumption for generations, back to the 1940s, and that plant-based varieties have had some influence on that, but are not a major driver behind lower liquid milk intake. By comparison, sales of fluid milk in 2022 totaled about 40 billion pounds. Plant-based sales totaled about 361.5 million pounds, or 11% of fluid milk’s total.

Alan Bjerga is executive vice president for communications and industry relations for the National Milk Producers Federation. He points out in recent research that while liquid milk sales have been slipping, so have plant-based beverage sales — even more so than milk. It’s a matter of more options cycling through the marketplace than ever before.

“The fact is there’s just more proliferation,” Bjerga said.

ERS research using household scanner data from 2013-2017 confirms that sales of these plant-based beverages are negatively affecting purchases of fluid cow’s milk. Still, the increase in their sales is much smaller than the decrease in sales of fluid cow’s milk, so plant-based milk alternatives can explain only a small share of overall sales trends.

Fast-forward to 2024, and the plant-based beverage options, displayed as “milk” in the United States, have exploded. You won’t just find the longstanding soy, rice and almond varieties. The cooler sections make room for cashew, coconut, flaxseed, hazelnut, hemp seed, macadamia nut, oat, pea , peanut, pecan, quinoa and walnut-based beverages. While soy has been in the market since about 1917, almond milk is now the leading plant-based alternative.

Foods often are covered in facts, figures and claims. What does it all mean? In this month’s Agweek Special Report, we look at food labeling, deciphering what things mean and don’t mean, what’s changing in food and agriculture, and how producers can stay on top of it.

While adding new plant-based beverages can involve adding different formulations of vitamins, sugar and flavorings to nuts, grains, seeds or legumes, dairy products are held to higher standards, Bjerga insists.

“If you took a whole tanker of milk and you added a glass of water to that tanker, by FDA rules, you wouldn’t be able to call it milk anymore because of that cup of water,” Bjerga said.

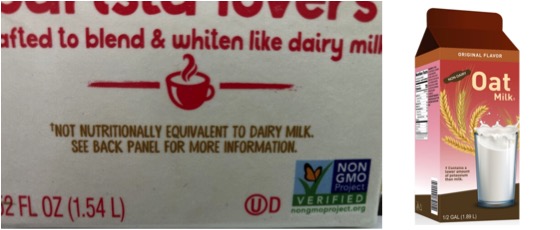

Bjerga feels it’s unfair that the two products can have such different formulations, yet still use the same “milk” label. On the shelf and in a glass, the two products look quite similar. Bjerga and many dairy advocates feel more needs to be done to differentiate between the two.

“Consumers are being misled about the nutritional content of these beverages because of the terminology that’s being used,” Bjerga said. In his role he communicates the importance of integrity in labeling on the industry, particularly the effect on dairy.

Dairy advocates say consumers should be able to trust that a label is telling them what’s inside that container. Bjerga said a fair amount of consumers are confused by the label to the point that they believe animal-derived and plant-based milk are providing similar nutritional benefits. Bjerga said that’s not the truth.

“Consumers have an expectation when they hear the word milk and they are not getting it from these imitators. And that’s good for no one,” Bjerga said.

Labels on food and beverage products give off a lot of cues to consumers. There are nutritional facts on the back of the product, but descriptions of important ingredients, names, logos and pictures that can all trigger a purchase are at the forefront. He said a consumer’s decision comes down to many things, but a fundamental part of the decision is the name on the product.

The National Milk Producers Federation takes a position on the subject that seeks to “stop the continued proliferation and marketing of mislabeled non-dairy substitutes for standardized dairy foods misrepresented as “milk,” “cheese,” “butter,” “yogurt,” “ice cream,” or other dairy foods.”

It’s an issue brought before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which defines milk as the product of an animal. Despite that being their definition, they do not restrict the use of the word “milk” when used on plant-based beverages.

The FDA performed a study of consumers in 2018 and three-quarters indicated they understood that plant-based milk products did not contain milk; less than 10% believed they did contain milk; and the remainder did not know. The focus group responses indicated that most people understood that plant-based milk was not animal-derived milk. It also showed that the respondents were familiar with the word milk with these products and preferred that name over other terms, such as “beverage” or “drink.”

Many consumers experience allergies to cow’s milk. Large populations are lactose intolerant. Some don’t want to consume an animal product. Consumers have a right to buy and consume whichever beverage works best for them.

But the integrity side of this is that the role of the FDA is to help inform consumers about the products they consume and to help them make a healthy choice, Bjerga argues.

“The current lack of enforcement of FDA’s standard of identity actually discourages that outcome,” Bjerga said. “And that’s why we’re fighting for the integrity of milk labeling because it encourages that.”

Bjerga said some of these beverage companies do a “frighteningly good” job marketing their product to make it look like it provides more nutritional value than liquid milk. Some do offer the nutrients consumers are looking for.

“We’ve also seen survey data showing clear majority of consumers believing that almond beverages have more protein than milk from a cow, when in fact it will often be one quarter or one eighth the amount of protein,” Bjerga said.

FDA guidance

In draft guidance from the Food and Drug Administration in February 2023, it was recommended that labeling should give consumers “the information they need to make informed nutrition and purchasing decisions on the products they buy for themselves and their families,” according to FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, in a release of the draft.

In their guidance they note that clarity is important because these plant-based beverages do not, in many cases, contain the nutritional value of liquid milk. The Dietary Guidelines only include fortified soy beverages in the dairy group because their nutrient composition is similar to that of milk, the guidance states.

Within the guidance, it recommends that a plant-based milk alternative product that includes the term “milk” in its name (e.g., “soy milk” or “almond milk”), and that has a nutrient composition that is different than milk include a voluntary nutrient statement that conveys how the product compares with milk based on the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service fluid milk substitutes nutrient criteria .

Some companies have added language to that effect.

This draft guidance remains the FDA’s current view on the subject.

“As you know, in February 2023, the FDA issued draft guidance, Labeling of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives and Voluntary Nutrient Statements, that provides our current view on the naming of plant-based foods that are marketed and sold as alternatives for milk,” an FDA spokesperson shared in an email response. “The guidance also includes our recommendations on the use of voluntary nutrient statements that would provide consumers with additional information to help them understand certain nutritional differences between these products and milk. We received approximately 1,600 comments from a range of stakeholders with many different viewpoints on various aspects of the proposal. The FDA is currently reviewing comments from the draft guidance and will work to finalize the guidance in the coming year.”

With the “milk” label still in use Bjerga said the dairy industry continues to push for the Dairy Pride Act , asking Congress to mandate that FDA deal with the “milk” label issue.

Lactose-free surge

Plant-based beverages are an option that many lactose-intolerant consumers purchase because they still want to enjoy a milk-like beverage even though their body tells them to avoid lactose. But one label that Bjerga is excited about is the “lactose-free” label appearing on more animal-derived milk products. It’s an area of liquid milk that is actually seeing significant growth in recent years as more consumers reach for the milk they enjoy, without the issues caused by lactose, which hits a large portion of the population.

“Lactose-free retail volume in 2023 was 239.2 million gallons,” Bjerga said. That’s up 6.7% from 2022. The lactose-free milk market makes up about 7% of the liquid milk market and it’s nutritionally identical, he adds.

Nutritional value

Dairy products offer nutritional value with protein and sources of vitamin A, D and B-12, as well as riboflavin, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, zinc, and calcium, according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service. Plant-based milk can offer many of these as well, as the drinks are often fortified with vitamins.

The FDA says that consumers should read the nutritional guidelines to determine if the milk alternatives are providing the nutritional benefits that they want or need.

“The nutrients you get from plant-based milk alternatives can depend on which plant source is used, the processing methods, and added ingredients, so check the label carefully,” said Susan Mayne, Ph.D., Director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in an FDA news release.

Bjerga feels that it’s still achievable to have the “milk” label issue resolved. In the meantime, Bjerga said the dairy industry is being proactive about another concerning label discussion — lab-based synthetic alternatives. Companies are now synthesizing a single dairy protein to make synthetic milk.

“We’re working hard to make sure they don’t get the sort of toe-hold that the plant-based folks got,” Bjerga said.