The significant scientific effort and VC investment in synthetic-biology-led dairy products ought to be of some interest in India

In the previous article (bit.ly/3oEccb2), we saw a short excerpt from a US patent on making “animal-free dairy” substitutes composed of mammalian milk proteins. The US Patents and Trademarks Office assigned it to Perfect Day Foods in 2018. Twenty-first century synthetic biologists are reconstructing lactation and photosynthesis; two core phenomena powering planetary biology. We also discussed the ability of animals to naturally customise their milk.

Evolution is slow, messy, and often inefficient. But studying mammalian lactation also shows us how evolution has resulted in remarkably fine-tuned solutions to problems. Consider the duck-billed platypus, an ancient mammal on the timeline of evolution, that still lays eggs; it has evolved a milk pad but not teats. As a result, its newborn sucklings are exposed to a large load and variety of microbes. Discovered only last year, an unusually potent antimicrobial protein, MLP (Monotreme Lactation Protein), found only in platypus milk serves to protect its babies from pathogens.

A key conceit of synthetic biology, with its intellectual origins in the engineering culture of MIT, is that we can now better nature. Professor Patrick Brown of Impossible Foods has frequently labelled animal farming as an obsolete, inefficient, and ultimately destructive technology in the food supply chain. Synthetic biology entrepreneurs like Perumal Gandhi and Ryan Pandya (Perfect Day) strive to make animal-free foods, like dairy, poultry, and seafood. Yet others strive to manufacture, at scale, esoteric materials like spider silk and horseshoe crab blood using the tools of synthetic biology. What enables this revolution?

The fact that there is a universal language of DNA common to all life forms enables the ongoing revolution of synthetic biology. Specific genetic sequences code for specific proteins. And this specific sequence is understood by even simpler organisms, like yeast for instance. Scientists in Kochi have published the sequence of genetic letters that instruct the Vechur cow to produce lactoferrin. If this sequence were to be inserted in, say, brewer’s yeast, then it will produce lactoferrin under the right conditions. More recently, Australian scientists sequenced the Platypus genome to precisely identify the code for MLP, the novel antibacterial protein.

Several synthetic biology entrepreneurs are attempting to build sustainable businesses in the vegan milk sector, broadly defined. They are taking approaches as different as chalk and cheese. Amongst the most ambitious approaches are the ones trying to grow cell cultures of the mammary organs themselves to secrete human and other mammalian milks. At the other end of the scientific and technological complexity spectrum are the so-called “plant milk” companies. Oatly, an oat-milk company has 2.3% of the global plant-milk market share and is valued at $12 billion. Several start-ups are attempting to make “animal-free” value-added dairy products such as cheese, and ice cream, by applying synthetic biology techniques for making milk proteins. At least one start-up is trying to re-constitute human breast milk with critical proteins made through synthetic biology.

Some common arguments generally made for an animal-free food supply chain are as follows: 1) Factory farming of animals has led to widespread antibiotic resistance because best practices in such factories required the extensive use of antibiotics. 2) Pandemics also have arisen on account of the high density of animals in the factory farms. 3) The vast amounts of concentrated animal waste also require careful disposal of nitrogen compounds into the environment. 4) Finally, the ethical alternatives offered by synthetic biology decrease animal suffering. Thus, scalable and sustainable animal-free systems to produce meat, milk and leather are popular investment destinations.

Perfect Day Foods, incubated at Rebelbio, an early synthetic biology incubator, has launched cow-free (initially, it was called muufri) ice-creams. The founders have been able to scale production of milk proteins, especially whey proteins, using synthetic biology techniques. They rely on re-programming a type of fungus called Trichoderma to produce these whey proteins. We have earlier seen how vegan burger-makers use plant-derived fats like coconut oil and palm oil to give it the necessary fatty flavors. However, companies like Perfect Day are exploring the possibility of re-creating fats of animal origin like butter through synthetic biology. Various microscopic algae are viable organisms for the scalable production of such fats.

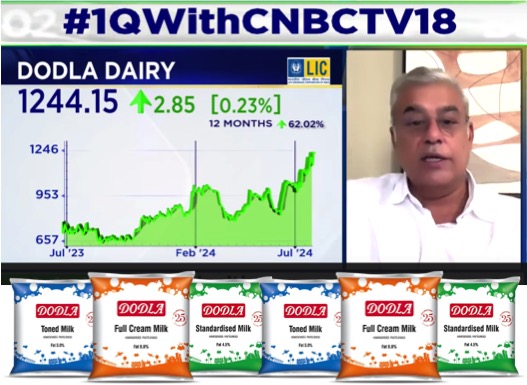

The intense scientific effort and large venture capital investments driving progress in animal-free dairy products made with synthetic biology ought to be of some interest in India. After all, India is the world’s largest dairy producer, with the largest number of cattle as well and a hundred million Similarly, the commercial success of synbio burgers and also synbio leather pique our interest. Is it possible that our humble dairy farmers might meet the same fate as our indigo growers of a hundred years ago?

Or does it behove us to protect the gene pool of the huge number of native breeds of cattle, and other animals? For, one day, like the strange duck-billed platypus, one of these animals will surely reveal vital secrets to our own well-being. We are, after all, the children of Bharata, who grew up playing with lion cubs and drinking milk with them.