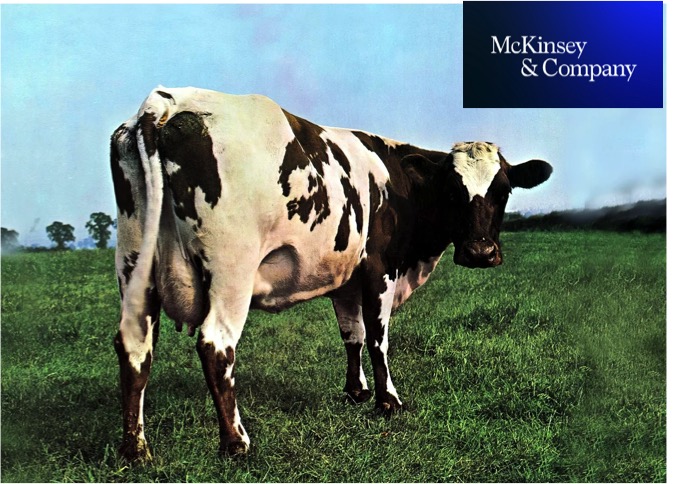

- Dairy farmers in Chittoor, known for its high milk production, are facing challenges due to extreme heat, which reduces milk output.

- Amid the challenges, a women-led initiative is helping the women farmers increase their income from the dairy business while addressing heat and fodder-related issues.

- With a women-centric supply chain, Shreeja offers purchasing milk at fair prices, supplying high-quality fodder, and providing access to veterinary doctors which support the dairy farmers in this drought-prone district.

On a hot day in late April, with the temperature reaching 43.2 degrees Celsius, M. Thayaramma, fetched pots of water from a nearby well. She washed her two cows in a shed just outside her home, located in the village of Atlavaripalli in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. The land near her house, where Thayaramma grows grass for cattle fodder is parched and devoid of life. The air is stiflingly hot and the sky is clear, with no sign of rain-bearing clouds.

Fifty-four-year-old Thayaramma has been a dairy farmer for over three decades and is well-versed in cattle care. But the unrelenting heat has become an increasing challenge, growing worse every year, she feels. The extreme temperatures cause a host of issues in livestock, from mastitis (inflammation of the udder) and dehydration, to fever and heat stroke, all of which reduce milk production. “Daily milk production has dropped by twenty percent in the past month,” she says, noting that she’s been washing her animals and providing them with water more frequently than usual to mitigate the effects of the heat. This reduction in yield typically happens in May and June.

Thayaramma is among the lakhs of dairy farmers in the Chittoor district. These farmers face a critical battle against heat stress, compounded by the scarcity of green fodder and water, which will likely continue for the next three months.

K. Ramanarao, a 50-year-old dairy farmer from Kannikapuram in Chittoor, has seen his daily milk yield from five cows drop from 50 litres to 35 litres. “Summer means more work and no profits for dairy farmers. To make matters worse, wholesale milk prices are low and there’s no support from the state government,” Ramanarao said. Another dairy farmer, 55-year-old K. Sriram from Velkur village, also in Chittoor district, sold his two cows in April and migrated to Bengaluru’s Naganahalli with his family to work as an agricultural labourer. Since Chittoor is located close to Bengaluru and Chennai, farmers move to the cities in search of better livelihood. “What else can we do? It is not like there are better employment opportunities in the district. We don’t have renowned factories here and most of the development is focussed on Tirupati, the neighborhood pilgrim district,” said Sriram.

Weather extremes making the dairy sector vulnerable

Andhra Pradesh ranks fifth in total milk production in India, and Chittoor is one of the state’s main dairy farming districts. Over the last few decades, Chittoor has undergone significant changes, including a shift in preference from buffaloes to cows. The proportion of cows in the district has risen from 8.56 lakh in 1999 to 9.60 lakh in 2017, while the number of buffaloes has declined from 1.44 lakh in 1999 to 0.88 lakh in 2017.

One of the major challenges Chittoor faces is its location in the Rayalaseema region, a drought-prone area with significant water scarcity. Rayalaseema, located in the southern part of Andhra Pradesh and sharing borders with Tamil Nadu to the south, Karnataka to the west, and Telangana to the north, experienced 15 drought years between 2000 and 2018. The drought in 2023 was the worst in over a decade and a half.

Now, in 2024, farmers in the region continue to face heat-related challenges. The El Niño effect and shifting wind patterns have led to harsher summers. Chittoor is experiencing above-normal temperatures, contributing to increased heat stress on dairy animals.

S. Karuna Sagar, a scientist at the India Meteorological Department in Amaravati, remarked that temperatures are breaking new records annually. “Due to the impact of El Niño, we expect high temperatures for the next two months,” he said, adding that the Animal Husbandry Department has issued an advisory to ensure keeping cattle cool by frequent wetting of cattle with water, during the summer.

Dairy farmers have expressed concern about cattle mortality due to heat stress and the associated costs of frequent veterinarian visits. Studies show that heat stress can reduce milk yield due to increased respiration rate, rectal temperature, and heart rate, affecting feed intake and, consequently, milk production.

Given these challenges, farmers are seeking government assistance. More than a decade ago, the United Andhra Pradesh government constructed sheds and supplied water and dry fodder to support dairy farmers, providing relief, locals claim. Dairy farmer Ramanarao recounted how he used to take his cows to a shed in L.B. Puram that housed 300 cattle for about three months. Veterinary doctors would visit regularly to ensure the cattle weren’t suffering from heat stress.

However, the farmers complain that no such support exists now. In 2021, the Animal Husbandry Department announced a similar initiative to combat drought, but it was not initiated in Chittoor, farmers claim.

An official from the Animal Husbandry Department in Chittoor, speaking on condition of anonymity, said, “Due to the election code, no schemes are in place.” Yet, dairy farmers claim there have been no schemes since the present government came to power in May 2019. The official declined to comment further when asked about the farmers’ complaints.

T. Narasimhulu, a 50-year-old dairy farmer, said that the only benefit he received in the past five years was a grass-cutting machine. “During summer, the government used to provide silage and dry fodder. But that hasn’t happened in the past five years,” Narasimhulu noted.

A women-led intervention

As heat stress exacerbates the challenges faced by dairy farmers, Thayaramma and others are finding relief through support from the Shreeja Mahila Milk Producer Company Limited (SMMPCL), the world’s largest women-owned and women-managed dairy company.

“Regular health camps help sensitise farmers to the harmful effects of heat stress. Veterinarians are available on call, sparing us the trouble of taking our cattle to the hospital for minor ailments,” Thayaramma noted. She is a board member and owns 36 shares of SMMPCL, established by the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in 2014.

Starting with 27 members in 2014 in Chittoor, Shreeja has expanded to 1.25 lakh members across twelve districts, including Chittoor. With a focus on enhancing women’s leadership and empowering them within the dairy sector in a drought-prone region, Shreeja offers numerous benefits, including purchasing milk at fair prices, supplying high-quality fodder, and providing access to veterinary doctors.

Beyond these benefits, Shreeja maintains a women-centric supply chain— from milk pooling to the sale of by-products — granting the women members shareholding and ownership in the company. Its two-tier governance structure comprises village contact groups, each representing seven members and member relations groups based on individual villages. Thayaramma said members can easily raise complaints or concerns with these groups or at milk pooling points.

Shreeja is also replacing plastic milk cans with steel ones and strengthening village contact groups that offer farmers valuable information. The organisation has a wide range of summer management initiatives. “Given the fodder shortage, we supply fodder seeds for free to our members — a kilo costs Rs. 100 in the market,” explained Rajendra Babu, Assistant General Manager of Shreeja. Each month, the company conducts at least 200 programmes to educate farmers on managing cattle during the hot season. “Any dairy farmer can access help from our veterinary doctors,” Babu added.

Babu further highlighted that Shreeja’s mission is to empower rural women, offer competitive prices to dairy farmers, and foster growth in the dairy industry through various measures. Shreeja’s members also receive dividends, bonuses, and incentives each year. “Farmers who supply more than 1,000 litres a year get a free five-litre milk can,” Thayaramma said.