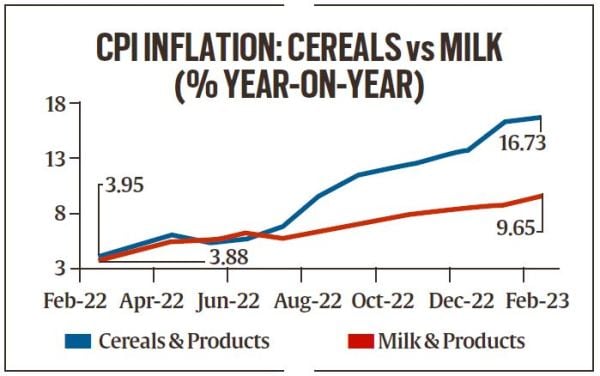

EVEN AS worries over cereal inflation are receding — with temperatures not rising as much to damage the standing wheat crop — it is milk that’s increasingly becoming a cause for concern.

he Karnataka Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation (KMF) has recently hiked the price of full-cream milk, sold under its ‘Nandini’ brand, in a rather unconventional manner. This milk, containing 6% fat and 9% solids-not-fat or SNF, was earlier costing consumers Rs 50 for one litre (1,000 ml) and Rs 24 for half a litre (500 ml). Now, they are paying the same Rs 50 and Rs 24 price, but it’s for 900 ml and 450 ml packs respectively.

Charging the same for lesser quantity is something that many fast-moving consumer goods companies have been doing in the last couple of years, whether for soaps, detergents, shampoos, biscuits or soft drinks. Such ‘shrinkflation’, through cutting pack sizes is, however, new to milk.

In this case, it has happened in a state where Assembly elections are due in May. KMF had, only on November 24, raised the prices of all its variants of milk by Rs 2 per litre. “They are being forced to because supplies have dried up. There’s shortage especially of fat, which has led them to increase full-cream milk prices and also stop sale of ghee outside of Karnataka,” said an industry source.

KMF is India’s second largest dairy concern, with its district unions procuring an average 81.64 lakh kg per day (LKPD) of milk in 2021-22, next only to the 271.34 LKPD by the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, better known as Amul.

“KMF’s procurement is down 9-10 LKPD compared to last year. They have now stopped supplying even to hotels and other bulk customers,” the source added.

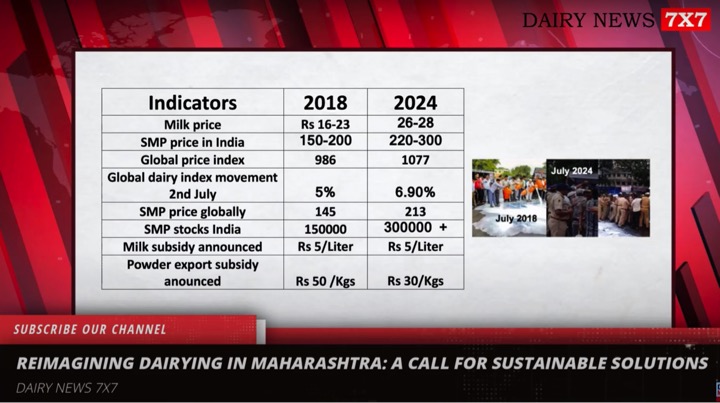

But it isn’t Karnataka alone. Milk is in short supply across India, also reflected in its consumer price index inflation touching 9.65% year-on-year in February. Although not as high as for cereals, the rise in milk inflation comes ahead of the ‘lean’ summer season, when production by animals would fall in the natural course. With demand for curd, lassi and ice-cream, too, peaking during April-June, the current shortfall could intensify – unlike in wheat, where the new crop will start arriving from March-end.

Last March, Amarsingh Kadam, a farmer from Sansar village in Indapur taluka of Maharashtra’s Pune district, was getting Rs 32-33 for every litre of cow milk (with 3.5% fat and 8.5%) that he was supplying to the nearby Sonai Dairy. This private dairy is currently paying him Rs 38-39/litre for the same milk. Kadam isn’t, however, too pleased: “My price has gone up, but I am selling only 250 litres daily now, as against 350 litres”.

Dashrath S. Mane, chairman of the Sonai Dairy, estimates milk procurement by dairies in Maharashtra to be 10-15% lower than last year. This is a result of high feed and fodder prices last year. Farmers responded by reducing herd sizes and under-feeding their calves or pregnant animals, which have turned out to be poor milkers. The drop in production, aggravated by the lumpy skin disease affecting cattle, came even as demand for milk returned with the post-Covid restarting of hotels, restaurants and canteens along with weddings and public functions.

The mismatch between supply and demand is also being seen in the prices of dairy commodities, especially fat/butter. During the April-July 2020 lockdown period, ex-factory rates of yellow (cow) butter had collapsed to Rs 200-225/kg. Today, Maharashtra dairies are selling it at Rs 420-425/kg. The buyers include Aavin (Tamil Nadu Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation) and other dairies in the South that are short of fat.

“Even Amul, Mother Dairy and the cooperatives in Punjab, Bihar, Jammu & Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have no surplus fat. They are having to buy white (buffalo) butter from dairies in the North,” said Ganesan Palaniappan, a Chennai-based dairy trader. While procurement prices of buffalo milk (6.5% fat and 9% SNF) have dipped somewhat over the last two months, from Rs 56-58 to Rs 52-54/litre, this may not last. The real crunch could come in the summer.