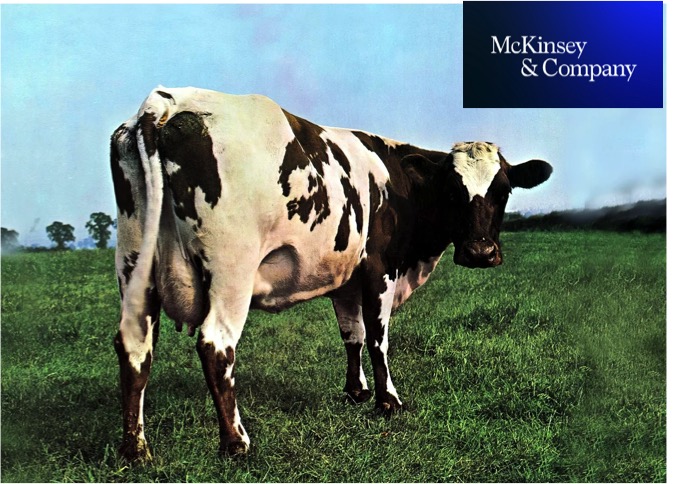

The first milk cooling tank in the European market to use CO2 as refrigerant in standard cooling systems of the direct expansion cooling type has been introduced by Wedholms. The tank is compatible with the revised F-gas Regulation that will be mandatory in the European Union from January next year. The DFC 953 range of milk cooling tanks is available for robotic milking with 1-8 robots and with capacity ranging from 3,200 litres to 30,000 litres. Synthetic refrigerants, such as hydrofluorocarbons, are currently being phased out by the European Union. According to the revised F-gas Regulation, recently signed into EU law, all new self-contained refrigeration equipment, with the exception of chillers, installed from January 2025 must use refrigerants with a GWP (Global Warming Potential) value of less than 150. Existing systems may still be used and repaired for the remainder of their economic life. However, effective from 2032, refrigeration systems using refrigerants with a GWP value above 750, apart from chillers, can no longer be refilled during maintenance and service. From 2027, further restrictions on the maximum amount of synthetic refrigerants that can be placed in the EU market will be introduced, capping the amount at around 20 million tonnes CO2 equivalent per year. This will increase the price of synthetic refrigerants, making milk cooling tanks with outdated technology more costly to purchase and operate, thus incentivising investments in milk cooling tanks using technology that is more modern and environmentally sustainable. “Refrigerants that are environmentally friendly are being introduced across the board and milk cooling tanks is no exception. Refrigeration is an essential process in the farming and dairy industries and we need to use processes that work in harmony with the natural environment that we depend on,” says Stefan Gavelin, managing director of Wedholms. Early refrigerants back in favour The phasing out of harmful refrigerants is a process that has been ongoing for nearly 40 years. During the 1980s, the first evidence of holes in the ozone layer started to emerge. Since then, successive regulatory regimes have heralded new product generations of refrigerants, each less harmful than the previous one. Early refrigeration systems, back in the 1800s, used natural refrigerants such as CO2, ammonia or hydrocarbons. However, these refrigerants were not practical to use with the manufacturing technology and safety practices used at the time. In the 1930s, freon was introduced, providing effective refrigeration at low pressure while also improving safety. Freon started to be phased out by the ratification of the Montreal protocol in the 1980s, due to its high ozone depletion potential. Since then, there has been a shift of focus back towards natural refrigerants again. CO2 has a GWP of 1 and an ozone depletion potential of 0, making its environmental impact neutral. “We are coming full circle, with natural refrigerants once again becoming the norm. CO2 refrigeration requires a high operating pressure, but thanks to technological advancements, such systems have, over the last decade, become viable for both commercial and industrial use, in many different applications.” “At Wedholms, we have chosen to work with CO2 as refrigerant. Ammonia is toxic as well as corrosive; hydrocarbons, such as propane, are flammable. CO2 have none of these disadvantages. In addition, it is readily available in large quantities and at low cost,” says Gavelin. |