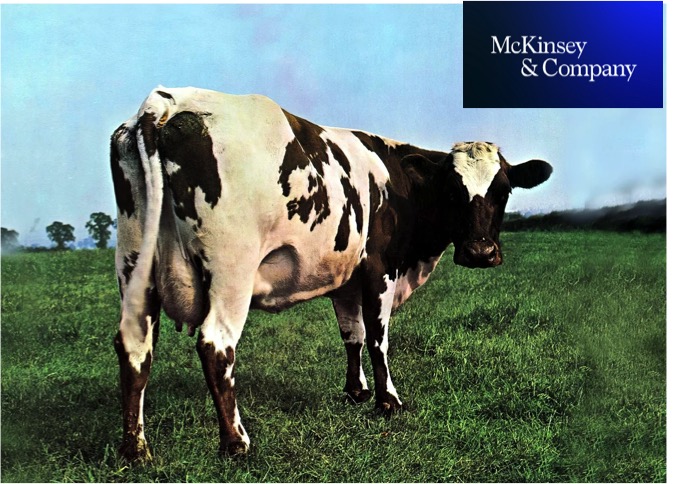

Dangi is a cattle breed native to the hilly areas of Maharashtra’s Nashik and Ahmednagar districts. The khoya made from its milk is so sweet that a popular Marathi saying goes: “You can be only as sweet as rajur (the word for khoya in Ahmednagar).” Yet, the breed might have become extinct without the efforts of scientists, farmers and local organisations.

Starting 2014, researchers from Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune, BAIF Development Research Foundation, New Delhi, local farmers and community organisations worked hard to make Dangi cattle rearing viable.

“When we started work, there were only small herds left,” said Sarang Pande of Lokpanchayat, a local organisation working in Ahmednagar. “The surviving cattle were also battling ailments due to changes in environment, cropping pattern and fodder. We started with proper vaccination of the surviving cattle.” Thanks to their efforts, villages in the region now have some young, thoroughbred Dangi bulls.

Meanwhile, multi-disciplinary teams of experts, community organisations and locals across Maharashtra are working to build the country’s first gene bank that will ensure Dangi and other native breeds of plants and animals don’t go extinct. The bank will store not only the hardy seeds of indigenous species and germplasm but also traditional knowledge.

In the Dangi project, for example, the traditional practice of ‘rakhan raan’ – setting aside grass and fodder for cattle throughout the year – played a key role. A ‘Dangi Parents Sangh’ was also started with 30 families in Akole taluka to rear purebred cattle.

“The efforts paid off and we now have purebred bulls. We are now trying to see how milk, cow dung and manure from the Dangi breed can be marketed. We want to promote it like Gir cows to revive this indigenous breed,” Pande said.

Bringing The Bank To Life

In the early 2000s renowned ecologist Madhav Gadgil had felt the need to conserve native and indigenous species of crops and other plants, and document oral traditions and knowledge associated with them. A pilot run from 2014 to 2019 proved successful, and last April, the Maharashtra government sanctioned Rs 179 crore to expand the project.

IISER faculty V S Rao, who is project director of the Maharashtra Gene Bank, said many local varieties of different living organisms are preserved by communities and individuals. “Farmers have generations of knowledge passed down orally about various plant and crop species. Our team’s effort is to preserve these pockets that still practise traditional methods, and the indigenous varieties that have survived due to their adaptive nature,” he said.

Seven Focus Areas

The gene bank project focuses on seven themes: marine biodiversity, crop genetic diversity, livestock genetic diversity, conservation and sustainable use of indigenous fish, conservation of grassland biodiversity, eco restoration of community forest resource lands, and economic plant species.

“We work with the locals and community-based organisations in each area. There are three national research institutions, two universities and 16 NGOs involved in the work. We have a tremendous gene pool in the country and it should not be lost since the indigenous species have adapted to the local environment and survived for many, many years,” Rao said.

The project also involves children. When schoolchildren were given a project to identify and name plants, animals and grass species around them during their holidays, “they came back with 200 varieties and collected seeds too.” “It helped them understand biodiversity and the effort required to conserve it,” Rao said.

Backup For The Future

Along with in situ (on-site) conservation, there is the gene bank in Pune where genotypes are kept as a backup and for reference. There are community-based seed banks at the local level where farmers can collect seeds and redeposit them after a harvest. Such seed banks are running successfully at Jawhar in Palghar taluka, Akole in Ahmednagar, and Bhandara district.

“These are commitment banks. A member can take a kilogram of seeds and return two kilograms. It’s a cooperative society managed by members. We call them genome saviours, and unique genomes are registered by the National Bureau of Plant Genetics,” Rao said.

Now, each group has identified expansion areas. For example, the livestock diversity group is looking at keeping the Katak breed of goats from Sangamner alive.