Milk has often been branded as a superfood as it is rich in most of the nutrients necessary for health. However, how milk came to be an integral part of the human diet has been a conundrum to scientists because most of the world can’t digest the product.

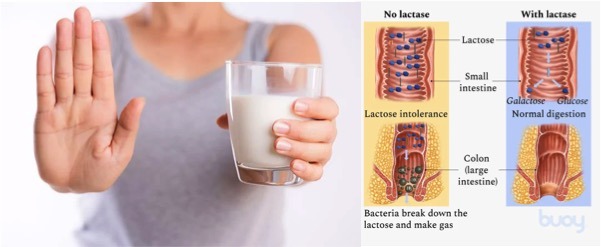

Studies on the global prevalence of this mutation suggest that 65% of humanity is lactose-intolerant, meaning they lack the gene to break down lactose into adulthood. Beyond the age of five, lactose, a sugar present in milk, cannot be naturally broken down in the stomach and this remains in the gut causing flatulence, acidity and diarrhoea.

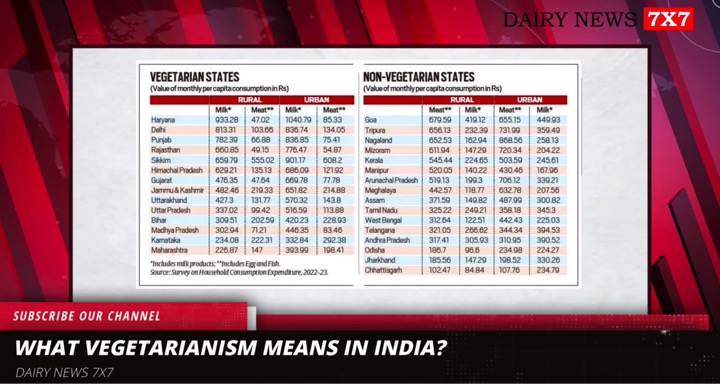

India is among the largest producers of milk and, by country, the largest consumer and it stands to reason most Indians possess it. However, multiple studies have shown that only around 18-25% have it.

Milk drinking, the story goes, hasn’t been very popular in the roughly 3,00,000-year history of humanity. But in the last 5,000 years, a genetic mutation enabled European pastoralists to produce lactase — an enzyme that breaks down lactose into a digestible form — well into adulthood, a trait called lactose persistence.

Genetic variant

Moreover, the genetic variant present in Indians is almost identical to that found in Europeans, meaning that it likely spread into India from migrant European populations. Thus, the standard story goes that something amplified the popularity of the genetic variant in Europeans and consequently in pockets of other continents.

Because evolution favours traits that confer benefits and eliminates those that don’t, scientists have long sought to explain why the mutated lactose gene became popular. Was it because European pastoralists, who herded cows, continued to drink milk despite the obvious discomfort because it was otherwise a viable source of nutrition?

A recent study in the journal Nature reports a multi-pronged analysis that suggests drinking milk was actually harmful in those who lacked the gene-variant but only in periods of famine and adverse environmental conditions. Thus, the gene flourished because it likely killed the Europeans who lacked it.

Professor Richard Evershed, the study’s lead author from the University of Bristol’s School of Chemistry, assembled a unique database of nearly 7,000 organic animal-fat residues from 13,181 fragments of pottery from 554 archaeological sites to find out where and when people were consuming milk. His findings showed milk was used extensively in European prehistory, dating from the earliest farming nearly 9,000 years ago, but increased and decreased in different regions at different times.

‘No connection’

Another team, led by Professor Mark Thomas, of the University College London, developed a statistical model and applied it to a database that showed the presence or absence of the lactase persistence genetic variant, using published ancient DNA sequences from more than 1,700 prehistoric European and Asian individuals. They found no relationship challenging the long-held view that the extent of milk use drove lactase persistence evolution.

An analysis of the UK Biobank data, comprising genetic and medical data for more than 3,00,000 living English, found only minimal differences in milk drinking behaviour between genetically lactase persistent and non-persistent people. Also, the large majority of people who were genetically lactase non-persistent experienced no short or long-term negative health effects when they consume milk.

“If you are healthy and lactase non-persistent, and you drink lots of milk, you may experience some discomfort, but you are not going to die of it. However, if you are severely malnourished and have diarrhoea, then you’ve got life-threatening problems. When their crops failed, prehistoric people would have been more likely to consume unfermented high-lactose milk — exactly when they shouldn’t,” he said in a statement.

Therefore, the authors argue that as populations and settlement sizes grew, human health would have been increasingly impacted by poor sanitation and increasing diarrheal diseases, especially those of animal origin. Consuming milk under these conditions would have been harmful to those who lacked the digestive gene.

“This situation would have been further exacerbated under famine conditions when disease and malnutrition rates are increased. This would lead to individuals who did not carry a copy of the lactase persistence gene variant being more likely to die before or during their reproductive years, which would push the population prevalence of lactase persistence up,” the authors note.