Here’s a quick quiz: What are the top three countries for milk production by volume?

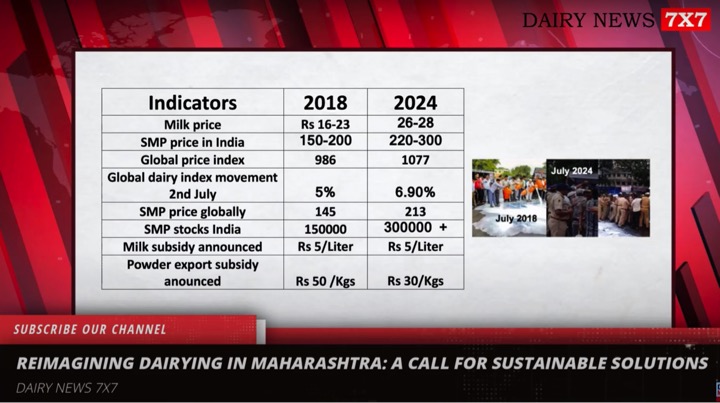

If you took a second to account for population and recalled a Milk House column from eight years ago about this country’s efforts to revitalize its dairy industry, you might have been able to put India at No. 1.

It might have been easy enough to slot the U.S. at No. 2, given its large farms and land space. However, did you come up with No. 3?

Believe it or not, Pakistan is the world’s third-largest dairy nation, with over 47 million tons of milk produced each year. Nonetheless, dairy farming in Pakistan looks much different than it does in North America.

Still to date, most of the milk in Pakistan comes from buffaloes. Unlike the American bison, the native buffalo breeds – Nili, Ravi and Kundi – are smaller, short-haired and have cow-like heads with thin horns curling up. These buffaloes, on average, give almost twice as much as the indigenous cattle. All 15 native Pakistani dairy breeds are from the Zebu species, with large humps and big floppy ears. Most dairy farms in Pakistan consist of only one or two buffaloes or indigenous breeds on subsistence farms that produce only for that family, which – and particularly adding in how little milk their animals give – makes the total output for the country even more impressive.

A Pakistani dairy farmer faces specific challenges, including hot weather, difficulty in attaining high-quality fodder and having to farm with low-producing animals. Still, commercial farming has risen near or in urban areas to supply populated areas with milk. Without the proper infrastructure to transport the raw milk or manufacture it into other goods, larger farms need to be located close to where it is going to be sold. However, in Pakistani agriculture, 10 animals constitutes a large farm, with only 7% of farms with herds larger than 50.

Likely the biggest change in the Pakistani dairy industry has been the import of Holsteins (and a few Jerseys). Being much more feed-efficient than the bulky native animals, the Holstein is seen as a central component to the modernization of the milk industry, with the largest commercial farms in urban areas consisting only of cattle from the U.S. or the Netherlands. Nonetheless, access to Holstein semen is limited and often expensive, capping the number of this foreign breed in the country.

Despite the hot weather and difficulty to grow crops – especially the farther one gets from the delta region that runs through the eastern part of the country – agriculture remains Pakistan’s most important industry, being its largest sector per GDP and employing 44% of its population. Nonetheless, the dairy industry in Pakistan has been described as being at a crossroads, looking to modernize and adopt some of the same practices and technology as some of the other major agricultural nations.

Without access to proper cooling technology, milk hygiene is a problem that plagues the industry. The heat makes it difficult for milk to be transported in rural areas, where it has to travel longer distances to be sold, raising the bacteria count. Sometimes the middlemen taking the milk from the farm to the market put ice in it, making it diluted by the time it reaches the customer. Often, only the morning milking on many rural farms gets sold, with the evening milking having to be thrown away.

As it stands, most Pakistani farmers, particularly in the rural regions, do not have access to knowledge of better farming practices, proper veterinary services nor financial services to help them expand. Companies like Nestlé Pakistan offer programs that seek to help farmers increase their production and move from subsistence to market-based farming, ultimately improving their livelihood, but progress is slow without a national commitment from the government. Having seen what the “white revolution” of India’s investment in their dairy industry has done for them, there is a belief that there is a great export potential for a country already producing so much under difficult circumstances.

Once a proper commitment is made by the Pakistani government to modernize the industry’s infrastructure, the country will one day be a major exporter of milk. When that happens, it will be a long-awaited moment for the Pakistani farmers looking to expand and unwelcome news for other countries competing on the international market. However, as it stands now, there is still major investment required at the national level in order to fully maximize the country’s ability to produce. Until then, farming in Pakistan continues to be an act of perseverance.