Recent studies have found the emergence of multi-drug resistant Salmonella tphimurium DT104 that causes infections in humans and cattle.

The rapid and unselective use of traditional antibiotics gives rise to the emergence of drug resistant phenotype in typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars, which has increased the difficulties in curing Salmonella-induced food-borne illnesses (majorly typhoid or paratyphoid fever, gastroenteritis, and diarrhoea) worldwide.

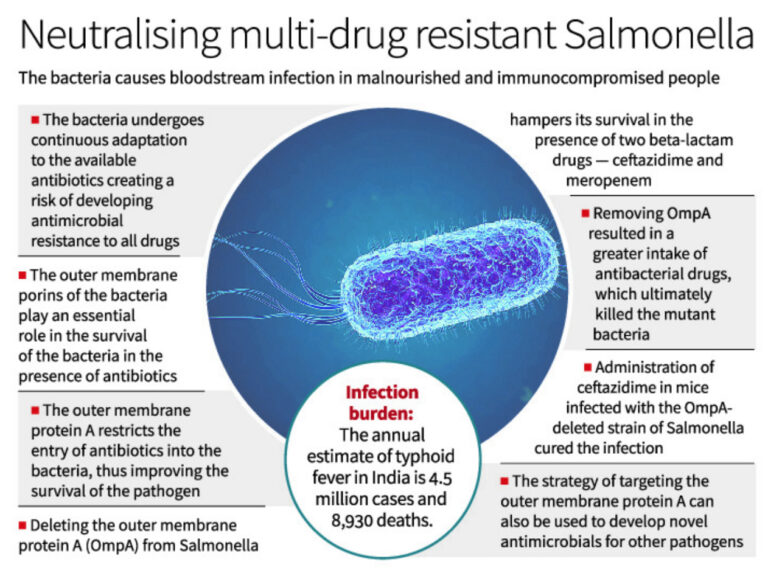

Salmonella typhimurium ST313, an invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella serovar, causes bloodstream infection in the malnourished and immunocompromised population of sub-Saharan Africa.

Recent studies have reported the emergence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) phenotype in Salmonella tphimurium DT104, which causes infection in humans and cattle.

Conferring protection

The MDR phenotype in this pathogen was provided by Salmonella Genomic Island-1 (SGI-1), which confers protection against a wide range of antibiotics, including ampicillin (pse-1), chloramphenicol/florfenicol (floR), streptomycin/spectinomycin (aadA2), sulphonamides (sul1), and tetracycline (tetG) (ACSSuT).

Further emergence of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) S. Typhimurium ST313 (having multi-drug resistant (MDR) and resistance against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and azithromycin) in Africa posed a significant threat to global health.

Recent studies reported an annual incidence of as many as 360 cases of typhoid fever per 1,00,000 people, with an annual estimate of 4.5 million cases and 8,930 deaths (0.2% fatality rate) in India.

The continuous adaptation of this bacteria to the available antibiotics creates a risk of developing antimicrobial resistance in the future. This is the reason why it is essential to study the effect of new drugs and find their potential targets in Salmonella in detail.

A recent study carried out by our group showed that outer membrane porins of Salmonella Typhimurium play an essential role in the survival of the bacteria in the presence of antibiotics.

The study was published in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy on September 30, 2022.

In this study, we showed that deleting outer membrane protein A (OmpA) from Salmonella hampered its survival in the presence of two beta-lactam drugs — ceftazidime and meropenem. OmpA is one of the most abundant barrel-shaped porin proteins localised in the outer membrane of Salmonella.

Absence of OmpA

The absence of OmpA in Salmonella hampers the stability of the bacterial outer membrane and reduces the expression of efflux pump genes.

The study further showed that the outer membrane protein A could restrict the entry of antibiotics into the bacteria, thus improving the survival of the pathogen under antibiotic treatment.

Removing OmpA resulted in a greater intake of ceftazidime and meropenem, which ultimately killed the mutant bacteria by disrupting its outer envelope.

Most importantly, this study showed that disruption of OmpA can also effectively reduce the antibiotic-resistant persister population of Salmonella.

Administration of ceftazidime in mice infected with the OmpA-deleted strain of Salmonella cured the infection and proved that OmpA plays a crucial role in antimicrobial resistance. This study is a continuation of another important research work published by our team in August 2022 (PLoS Pathogens), which delineated the role of Salmonella OmpA against the nitrosative stress of host macrophages. The loss of integrity of the bacterial outer membrane in the absence of OmpA made the bacteria highly susceptible to killing by the host’s innate immune system.

Other Gram-negative pathogens (Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, etc.) use outer membrane porins for various purposes, ranging from maintaining outer membrane stability to developing antimicrobial resistance.

Reducing AMR risk

As demonstrated in our study, the strategy to target outer membrane protein A (OmpA) of Salmonella can also be used to develop novel antimicrobials for other pathogens that can effectively reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the future.