With some consumer companies reporting poor September quarter numbers, stock market investors are being fed many interesting theories about the state of the Indian economy and consumers.

Are rising rents prompting folks to skimp on their daily bread and cookies? Are sluggish Maggi and Kitkat sales a sign of a middle-class squeeze? Should patchy sales of salt and tea be laid at the doors of a late-staying monsoon? Some FMCG companies would have us believe so.

But what if setbacks to some product categories are the result of changes in consumer preferences?

An analysis of macro data on consumption for the last 10 years shows that many of recent setbacks to FMCG companies could be the result of changing buying habits. We unearthed these shifts in consumption from macro data.

From goods to services

While tallying your household bills, have you noticed your spending on travel, entertainment, healthcare and education taking away a bigger chunk of your earnings than basic roti, kapda and makaan spending? This is par for course as incomes rise.

National income data show that consumer services are increasing their share of household budgets, reducing allocations towards basic goods. National Accounts data recently released by MOSPI capture item-wise private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) of households between FY12 and FY23. Mining this data reveals a noticeable shift in consumer spending from goods to services.

Between FY13 and FY23, India’s aggregate PFCE in nominal terms grew at the rate of 11 per cent a year from ₹56.5 lakh crore to ₹164.2 lakh crore. This period has seen spending on consumer services expanding much faster than goods.

In FY13, goods such as food products and beverages, clothing and footwear and household appliances made up the lion’s share of PFCE at 53.3 per cent while services such as house rent, healthcare, education and financial services made up a lower 46.7 per cent.

By FY23 though, services including rent, healthcare, education, communication, financial services etc had expanded to 49.1 per cent of PFCE while goods reduced their share to 50.9 per cent.

This subtle shift in share-of-wallet has meant very large differences in growth rates for services versus goods. Consumer spending on services has expanded by 212 per cent in absolute terms from over ₹26 lakh crore to nearly ₹81 lakh crore in these 10 years, while that on goods has grown by 180 per cent from ₹30 lakh crore to ₹84 lakh crore.

Transport and communication services (18.1 per cent of PFCE in FY23) now see nearly two-thirds the spending on food and beverages (29.5 per cent). Consumers spend more on healthcare (5.1 per cent) than gas, electricity and water (4.1 per cent). Education is grabbing a bigger share of wallet (up from 3.7 to 4.5 per cent), while clothing and footwear gets a lower share (down from 6.3 to 5.4 per cent).

This is likely to lead to listed consumer services companies seeing better growth rates than sellers of staples such as FMCGs.

Covid changes habits

After Covid, did you switch to cooking more at home and splurging on entertainment? This is also a nation-wide trend.

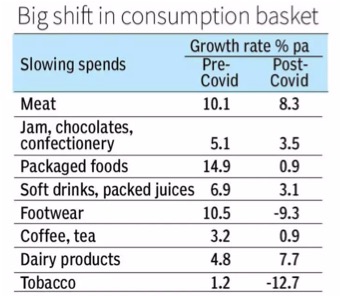

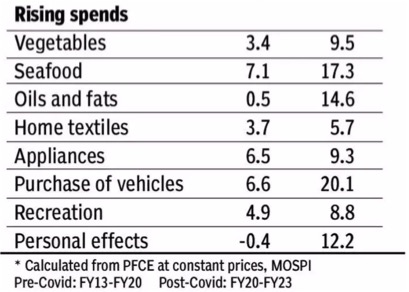

Breaking down PFCE data (in real terms) into the pre-Covid years of FY13 to FY20 and post-Covid years from FY20 to FY23 shows that Covid triggered some major shifts in consumer habits.

Some of these relate to food preferences. Consumers seem to have cut back on purchases of packaged products such as jams, processed foods and soft drinks to buying more vegetables, dairy products, cooking oils and seafood. Redoubled focus on health saw a sharp cutback on tobacco use.

Lock-downs seem to have created a yen for entertainment as also for owning personal vehicles, appliances and sprucing up the home (See table). This is likely to have led to some spending categories (and listed companies) losing out while others gained at their expense.

Comfortable with borrowings

The YOLO (you only live once) philosophy that has seen Indian consumers splurge on services, has seen them get quite comfortable with loans too.

National income data show that as Indian households expanded their routine spending at a 11 per cent nominal rate between FY13 and F23, they also acquired homes and invested large sums in financial assets.

Between FY13 and FY23, Indian households managed to nearly treble their investments in financial assets from ₹10.6 lakh crore to ₹29.7 lakh crore and while more than doubling their investments in physical assets, mainly residential homes, from ₹14.6 lakh crore to ₹34.8 lakh crore.

Incomes and household savings (which expanded from ₹22 lakh crore to about ₹50 lakh crore in this period) were simply not enough to bankroll this buying binge, prompting them to take on loans. Household liabilities have thus galloped much faster than assets in the last decade, shooting up over fivefold from ₹3.3 lakh crore in FY13 to ₹15.6 lakh crore in FY23. The climb in loans has been particularly steep after Covid.

The small minority of folks who borrowed to invest in stocks or mutual funds may be sitting pretty today, because stock markets have trebled in value since Covid. But for most others, the borrowing binge will have resulted in a sizeable EMI (Equated Monthly Instalment) outgo not matched by a growth in assets.

Given that this borrowing binge is of recent origin (household loans doubled from ₹7.4 lakh crore in FY21 to ₹15.6 lakh crore in FY23) and has coincided with RBI raising rates, EMIs would have begun to pinch households only recently.

This appears to be a more plausible explanation for the recent urban consumption slowdown than vegetable inflation or a shrinking middle class.