For humanity, antibiotics are a huge blessing. Antibiotics have saved millions of lives from bacterial infections. However, there is growing concern that these bacteria will become resistant to the drugs we use against them.

When we think about antimicrobial resistance, we often focus on what drugs humans take. We might not even consider the use of antibiotics in livestock, but they also pose a threat.

In fact, much more antibiotics are given to livestock than to humans. Researchers previously estimated that, in the 2010s, around 70% of antibiotics used globally were given to farm animals. While there hasn’t been an update of these figures in the last few years, it’s likely that more antibiotics are still used in livestock than humans.

Overusing antibiotics in livestock increases the risk of disease in animals and humans in several ways. First, antibiotics are often used as a cheap substitute for basic animal welfare practices, such as giving animals enough space, keeping their living environments clean, and ensuring that barns are well-ventilated. A failure to maintain hygienic conditions on farms increases the risk of disease for both livestock and humans.

Second, the overuse of antibiotics can also increase the risk of bacteria that are resistant to treatment. That threatens the health of the animals but can also be a risk for humans for crossover diseases.

Finally, humans can be exposed to resistant pathogens by eating contaminated meat and dairy products.

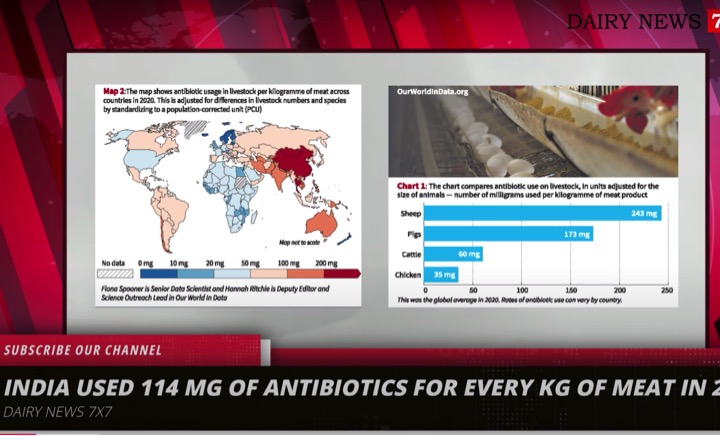

One of the key challenges in understanding the extent and risks of antibiotic resistance in livestock is the lack of transparent data sharing from countries. Of course, comparing the total amount of antibiotics given to cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens would be unfair. Cows are bigger than chickens, so we would expect them to need more antibiotics for the same impact. So, researchers compare antibiotic use in units adjusted for the size of animals — usually as the number of milligrams used per kilogramme of meat product.

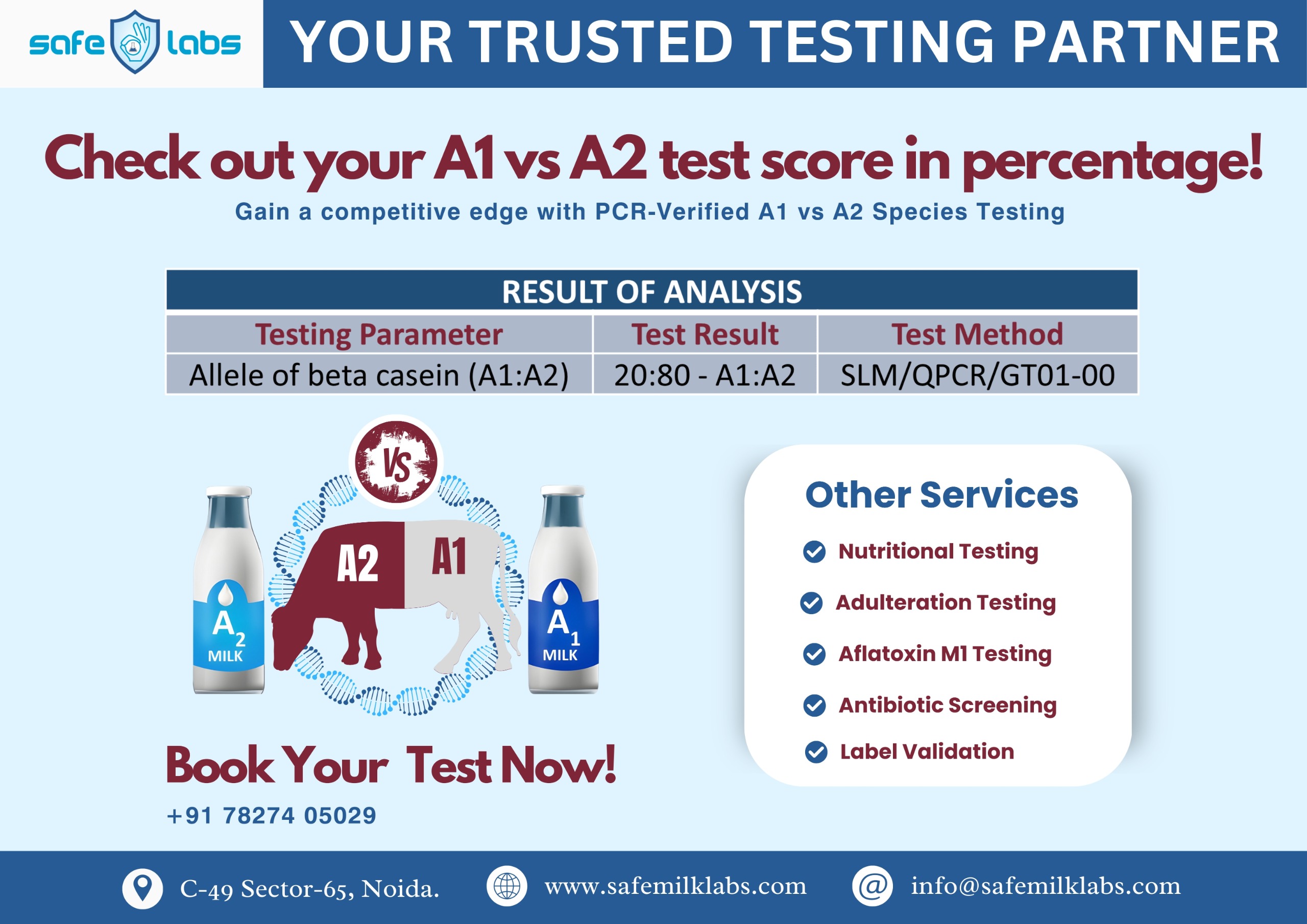

Chickens tend to receive the least antibiotics. You can see this in Chart 1: they receive about seven times less than sheep and five times less than pigs. Cows also receive less than pigs and sheep.

Antibiotic use is measured in milligrams per kg of animal product. Sheep have the highest usage at 243 mg, followed by pigs at 173 mg, cattle at 60 mg, and chickens at 35 mg.

One of the reasons why antibiotics are used in lower quantities in chickens is that they are killed at a much younger age. Fast-growing breeds reach their “slaughter weight” at around 42 days, so they are often slaughtered when they are just 40 to 50 days old. Since their lifespan is shorter, they consume fewer antibiotics. Pigs are usually slaughtered when they are around five to six months. The fact that intensive livestock get far more antibiotics than animals raised outdoors is one reason why cows tend to get less antibiotics than pigs.

Of course, the exact amount of antibiotics given varies across countries. Researchers Ranya Mulchandani and colleagues estimated antibiotic use across the world based on the best available data, as well as extrapolations for those countries that don’t release data.

Map 2 shows antibiotic usage in livestock per kg of meat in 2020. Asia, Oceania, and most of the Americas use a lot of antibiotics. Europe and Africa, in blue, tend to use less than 50 mg per kg. For instance, India used 114 mg of antibiotics in livestock per kg of meat in 2020, compared to 4 mg in Norway — 30 times less. Of the 190 countries for which the data was collected, India ranked 30th in terms of antibiotic usage in animals. There are a few reasons why these differences are so large.

The first one is affordability and access: farmers in Africa, for example, have less access, just like they have less access to other farming inputs, such as fertilizers.

Another reason is the differences in regulatory and industry norms regarding antibiotic use. Antibiotic use has dropped significantly in Europe, partly due to regulation.

Finally, the most popular types of livestock make a difference. As we saw earlier, sheep and pigs tend to receive far more antibiotics than cattle or chickens, even after adjusting for their size. That means countries that raise many pigs would tend to use more antibiotics. More than half of Thailand’s meat supply is in the form of pig meat. In China, it is two-thirds. That’s more than the global average of one-third.

Some countries have reduced antibiotic use a lot. Antibiotics can play an important role in preventing disease and illness in animals. This is no different from humans. So, removing them completely is not necessarily the best option.

The key is to use them more effectively: changing farming practices to reduce antibiotic use where it’s in excess or using antibiotics in smaller quantities when it is needed. Many antibiotics given today are not used to prevent disease but to promote growth and produce meat more efficiently.

We know countries can reduce antibiotic use while maintaining healthy livestock sectors because some countries have already achieved rapid reductions. Between 2011 and 2022, sales of veterinary antibiotics fell by more than half across several European countries. The use of antibiotics considered critically important in human medicine also fell by half, with some specific drugs falling by 80% to 90%.