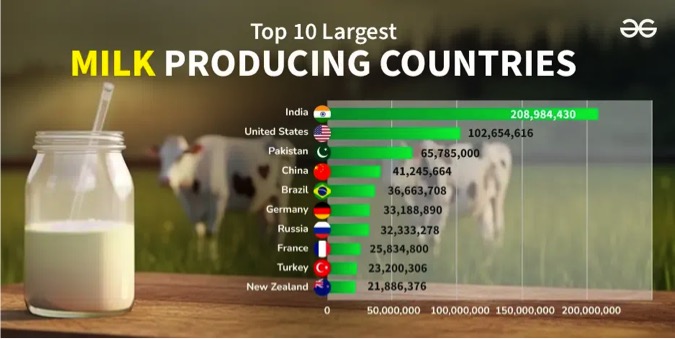

A group of scientists has concluded that ancient Europeans drank milk for millennia despite the digestive problems it may have caused, casting doubt on theories on how humans evolved to tolerate it.

Scientists have long speculated that an enzyme needed to avoid any gastrointestinal discomfort developed rapidly in populations where domesticating dairy animals was prevalent.

People who could tolerate milk, that theory goes, gained a new source of calories and protein and passed on their genes to more healthy offspring than those without the genetic trait — known as lactase persistence — that allows themto digest the sugar in milk into adulthood.

But a new study has offered a radically different theory, arguing that side effects such as gas, bloating and intestinal cramps weren’t enough on their own to move the evolutionary needle on the genetic mutation.

“Prehistoric people in Europe may have started consuming milk from domesticated animals thousands of years before they evolved the gene to digest it,” the study’s authors said.

The study, published in the journal Nature, was produced in collaboration with more than 100 scientists across a range of fields including genetics, archaeology and epidemiology. The scientists mapped out estimated milk consumption in Europe from approximately 9,000 years ago to 500 years ago.

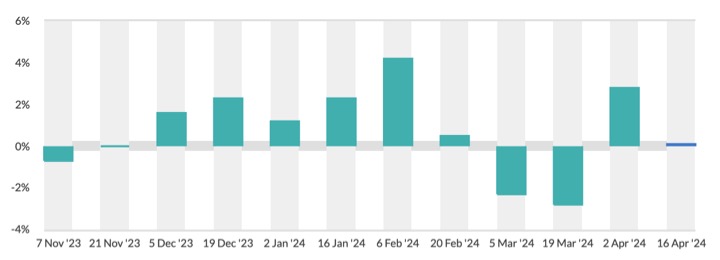

By analyzing animal fat residues in pottery from hundreds of archaeological sites, alongside DNA samples harvested from ancient skeletons, the researchers concluded that lactase persistence was not common until around 1,000 B.C., nearly 4,000 years after it was first detected.

And, rather than in times of abundance, they argue that it was during famine and epidemics that having the mutation became critical to survival: when undigested lactose could lead to serious intestinal illnesses and death.

Using archaeological records to identify periods where populations shrank, they concluded that people were more likely to drink milk when all other food sources had been exhausted, and that during those periods, diarrhea was more likely to escalate from a mild to a deadly condition.

George Davey Smith, an epidemiologist at the University of Bristol, who teamed up with the researchers on an analysis of contemporary data on milk and lactase persistence in current populations, said the study raises “fascinating questions” about whether some people who believe they are lactose intolerant “might actually be fine if they drank milk.”

About a quarter of Americans are lactose intolerant. In a lawsuit filed last year, a group of American doctors asked why the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s dietary guidelines recommend so much dairy — suggesting that the federal agency is looking out for the interests of the meat and dairy industries rather than the health of Americans.

USDA dietary guidelines are driven by milk marketing concerns — not nutrition — lawsuit alleges

Previous studies have suggested that populations had to rely heavily on dairy before individuals adapted to tolerate it in abundance. A smaller study in 2014 found the variation that allows humans to digest lactose didn’t appear in Hungarian DNA samples until 3,000 years ago, whereas it may have cropped up as far back as 7,000 years in places such as Ireland where cheesemaking became abundant.

Amber Milan, an expert in dairy intolerance at the University of Auckland, said the idea that the lactase mutation became important to survival only when Europeans began enduring epidemics and famines is a “sound theory” and “supported by previous research of drivers of genetic selection.”

She added, however, that she is not sure the new study “entirely rules out that widespread milk consumption was the evolutionary force behind lactose tolerance” — partly because the genetic data was collected from Biobank, a British biomedical database of genetic and health information from some 500,000 people.

The authors have also focused on the major European genetic variant for lactase persistence — which, while appropriate for this study, “does potentially miss other genetic variants that result in lactase persistence,” Milan said.